There was a moment towards the end of the new Hellraiser when I settled into the fact that they weren’t gonna nail it. The villain—whom we’d seen at the beginning, begging Leviathan for the gift of “sensation”—was recounting what happened when said wish was fulfilled. Bear in mind, while he was relating this story, he was hunched over with what appeared to be a Fabergé accordion jammed in his chest, so this reveal wasn’t about surprise. This man, a wealthy art dealer who’d experienced so much that he was down to begging octahedral space gods for a new buzz, was blessed with a gizmo that twisted his nerves every few minutes. As it lowered from Leviathan’s gift shop, the relative lameness of this was made apparent and, worst of all, we didn’t even get to see it installed. Just a few sound-effects were our treat, and after they promised us such sights.

The long horror franchise is synonymous with steep declines in quality, and the Hellraiser series is no exception. In terms of entries, it’s the second longest with 11, behind Halloween’s 12 (I don’t count Season of the Witch, as it doesn’t feature Michael) and one ahead of Friday the 13th (I don’t count Freddy vs Jason as it’s more a .5 for each of them). The oft suspected and frequently true reason for the later entries’ lack of quality is a cynicism in the film’s production that seeks only to crudely ape previous instalments in the hope of making some money, but this isn’t always the case. Sometimes, people are genuinely wanting to make a great film that respects the franchise but still fail to get above a collective 49% on Rotten Tomatoes. This is because nailing this is a lot harder than it looks, so hard, in fact, that no film in the Hellraiser franchise has ever managed it.

Now all we need… is skin

Horror is an incredibly mechanical genre because its success condition is comparatively narrow. A well-made drama can be funny, sad, poignant, or really anything besides terrifying, giving audiences dozens of elements to find appealing. Even with the different approaches afforded by the growing breadth of non-comic horror subgenres, they all aim to scare, and the means of accomplishing this are far more finite than one may think.

A big thing running at you, possibly wielding a sharp thing, is a popular choice for horror because it stimulates the threat response built into most complex brains, so it’s unsurprising that the murderous monster genre is one of horror’s most common forms. A complex, creeping build has a lot of potential failure points that “big thing running at you” doesn’t, and when your work hinges on a single success condition, the simple choice is an understandable one.

There’s a subgenre difference between a monster movie and a slasher but the narrow success window means there isn’t really a mechanical one. This is most obvious when you compare non-human entities, like the Xenomorph, to human threats like Michael Myers, Leatherface, and Jason (though some eventually added mystical monster elements). Granted, Leatherface doesn’t lay eggs in you, but that’s a spice added to a basic dish of pursuing and killing you without a semblance of human thought.

There are some who may look like exceptions, but even these prove the rule. Scream’s Ghostface is very much a human/s who can appear perfectly rational when needed, and Freddy Krueger is anything but mute. But Freddy, while conversant, is a malignant revenge spirit, a fundamentally inhuman monster whose murderous motivation is as much a part of his spectral DNA as the xenomorph’s instincts are to it. Original Ghostface was two high-school guys you could talk to, make laugh, and who’d sometimes talk to their victims, but these were all distinctly separate moments which were part of the film’s mystery component. We heard him speak, but when Ghostface was killing he was as much a mute monster as the others.

Monster movie villains must act as unknowable forces to keep semantic data from interfering with primal reactions. This is why monsters/slashers have motivations, but not reasons. An insane killer you can talk to collapses the mystery and engages ideas like bargaining which tampers with the threat. I have better chances of talking my way out of getting killed by Dr Hannibal Lecter than I do with a Xenomorph, so while the good doctor may be creepy, sinister, or disgusting, an old man isn’t going to trigger fight or flight reactions like a Swiss beetle monster. The unknown and unknowable shrinks us and reduces our sense of control, while a design that emphasises primal triggers like size, sharp, or sometimes “distant other” (insectoid shapes, tentacles, disease) clarifies the lack of control into a fear response.

These are a lot of closed logic gates, which results in a deeply rooted structural homogeneity in monster/slasher movies to the point that many could serve as sequels to each other with just a change in mask. And change masks is what most of them did.

Do I look like someone who cares what god thinks?

The first modern slasher/monster movie is 1978’s Halloween, with other notable franchise firsts Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street arriving in 1980 and 1984 respectively. By the time Hellraiser came out in 1987, Halloween and Elm St were on their third entries (each with a fourth about 10 months away), Friday the 13th was on its sixth, and dozens of lesser-known entries had tried to break into the market in between. Some of these lesser-knowns are very good, or at least comparable to later franchise sequels, but few of those have a sequel let alone ten, so what made Hellraiser stand out?

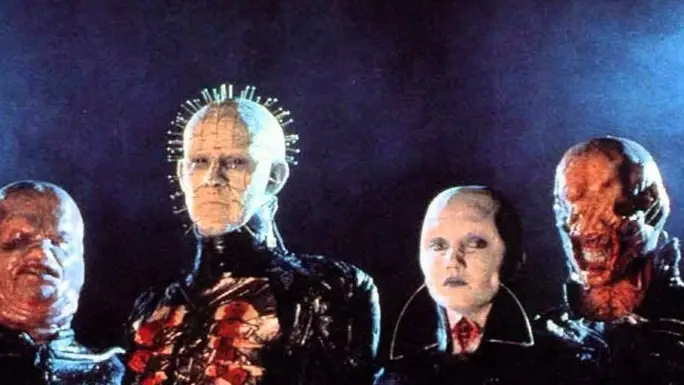

Pinhead’s not Pinhead’s name, even though we all call him it, so the most obvious answer to the above question is in design. There’s another common thread shared by long horror franchises and that’s the iconic. Be it the obvious villain mask or something like Final Destination’s Rube-Goldberg machines, the hook the series hangs on is immediately identifiable and in this the Hellraiser series is among the best. From the Lament Configuration to the Cenobites themselves, the series has created some of the most instantly recognisable visuals in horror. But there are lots of great horror movies, masks, and monsters without eleven film entries and not always because of scrupulous care for the artistic value of the property protecting them from lazy cash-ins.

The thing about the iconic is it’s still just a change in mask. A different coloured Froot Loop can only fool you for so long, before the fundamental sameness of them turns an entire genre into a mouthful of sugary mush. What made the Cenobites instantly stand out from just another loop of sugar was deep structural changes to who they are and what they do.

The suffering of strangers, the agony of friends.

Michael Myers doesn’t express anything. Jason Vorhees doesn’t have a favourite show. There is no point where a Xenomorph would stop to spare an autistic child. The most any of these things are is a force of rage or instinct. One could never imagine asking any of these things who they are, yet that’s exactly what Kirsty does when she first meets the Cenobites. It strikes me as an odd question to ask a group of beings that have appeared to menace me in a dimensionally shifting hospital room, curious as I may ultimately be, but odder still is that she gets an answer. Even odder than that is that the answer is an honest one.

The more talkative killers may use that opportunity for a quip, “YOUR DOOM”, or some other threatening line (a Krueger staple and something Ghostface would certainly do over the phone), but the Cenobites immediately stand out when Pinhead replies, “Explorers in the further regions of experience”. Chatterer has his fingers in my mouth, that lady over there is fingering a tracheotomy, you have a head full of pins, and you’re explorers? He then goes on to say, with a note of anger, that they are “demons to some”, then noticeably brightening when he adds, “angels to others”. They’re here because you asked them to come. They’re offering pleasures. They’re only as annoyed as I would be if you asked me to come over to your house to move a fridge, and I travelled all the way over to there to discover you don’t even have one.

This moment crystalises what makes the Cenobites stand out, earn ten sequels, and remain respected horror icons even as those sequels continued to be released. It’s also why these movies are fundamentally flawed.

The mind is a labyrinth.

The core of what makes the Cenobites’ stand out is contradiction. They are iconic horror monsters whose mere appearance terrifies, any movie would be happy to have them chasing some poor girl around, except they’re not monsters. They rip flesh from muscle with hooks, torture souls for eternity, and warp people into nightmarish creatures, but only if the victims ask them to. You can’t hurt them, you can’t hide from them, and they can appear anywhere, but only if you go out of your way to solve a puzzle box. They cause pain so unimaginable it needs its own dimension, but to them it's a pleasure they hope to share. They are the only movie monsters who care about consent.

Most people aren’t neglectful camp counsellors, Space Marines, or dream warriors. Most people don’t go poking about rural Texan farmhouses. Most people don’t have the complicated family history that may draw the attention of any number of masked serial killers. It’s pretty hard to meet one of these things, and even with that competition, one has to go insanely out of their way to ever meet a Cenobite.

When was the last time you even saw a puzzle box let alone solved one? I may sign up with the Earth marines or Weyland-Yutani just to improve my lot in life, but even that is simpler than researching, finding, affording, and solving an antique puzzle box. If you do all that, you have some idea of what to expect and the degenerately horny experiencing buyer’s remorse don’t exactly make sympathetic victims. I know people who enjoy being publicly flogged, and they know suspension artist people. For these types, being hung from the roof by hooks while a pale leather guy says a bunch of weird shit is a Saturday well spent, so what’s the movie there? Where’s the tension? How does an audience translate fear onto themselves when that fear is just nerves before a transformation they end up appreciating? Watching a deranged pervert get their heart’s desire is more documentary than horror.

This is the primary struggle of a Hellraiser movie, and while there are absolutely some that are better than others, it’s not a struggle any have won.

A Hellbound Start

The first Hellraiser knows this problem intimately and doesn’t make the Cenobites the villains at all. They’re more the referees in a fight whose participants—one of the aforementioned degenerately horny types, Frank, and the sympathetic victim, Kirsty—wind up making them near heroes who mete out a well-deserved punishment. Pinhead warns Kirsty that what they’re about to do to Frank, “…isn’t for your eyes” and even stop him from harming her, before ripping the evil villain of the past 82 minutes of the movie to pieces. The film should have ended here, because the next ten minutes really go to shit.

The actual monster of the movie, Frank, is gone, but these monstrous entities are still here, so the movie spends the next few minutes treating them like they’re standard slasher monsters and not the unique, near helpful beings they were just moments ago. For absolutely no reason, the Cenobites decide to menace Kirsty. She then grabs the Lament Configuration and proceeds to use it like a weapon by repeatedly solving it at the Cenobites, dismissing them with some classic 80s special effects and one-liners. Well, except Butterball who has a house fall on him.

Some may argue that the betrayal fits the characters and was always part of Pinhead’s plans, even though there’s no actual evidence for that and the “your eyes” warning directly suggests otherwise. Even then, the rest of this is still baffling garbage. Seriously, have you ever solved a puzzle box or one of those physical puzzles you get from weirdo nerd stores? Now try solving this under the kind of stress you’d feel if failure in the next ten seconds meant an eternity in a hell dimension. Destroying the monster/thing with the new weapon/Jesus is a classic trope, and lots of fun when used effectively, but rapidly solving a puzzle at monsters is stupid and doubly so when Kirsty unsolves the puzzle just to solve it again. The established lore is that the box opens a door, so wouldn’t returning the box to its original setting close the door and banish them all at once? Is Butterball vulnerable to houses or is he unable to move because he’s too busy orgasming under a pile of rubble? Why doesn’t he need to be unpuzzled back to the hell dimension? All of this is incredibly stupid because it’s the wrong trope structure clashing with established character and plot.

The entire sequence smacks of studio interference and demonstrates the problems with treating the Cenobites like they’re standard monsters.

We're already here... and so are you

Its sequel, Hellbound, starts with a few good ideas. Using the message from her father gives Kirsty an active motivation that brings her into inevitable contact with the Cenobites but in a way that maintains her innocent victim status. In turn, this extra contact, though it winds up being part of a trick, is enough to motivate Pinhead to see her presence as less than an innocent accident. Through this, his pursuer role stays true to his fundamental character of wanting to share forbidden pleasures, like a gimp Pepé Le Pew, and not just as a mindless torturer with no rules. Setting some of it in the labyrinth was a good choice, as it can be a source of mood, other threats with fewer scruples, and other motivations like escape.

The film’s final act begins with the sinister Dr Channard getting his wish and becoming a Cenobite. This is one of the better moments in the whole film series as it wonderfully summarises the entire process. Channard is a sick man who killed animals as a child and tortures his patients, the exact type of maniac who’d seek the puzzle box, but he’s still human so the sights of the Labyrinth scare him, and he screams as the process begins. When returned, with his own leather outfit and torture items, his line, “And to think, I hesitated” is a classic because few monstrous transformations come with such a coherent epilogue. He was hesitant, but definitely happy with his choice which cements the point about Cenobites being willing participants. There’s missing information on what happens next, as there were filming issues, so there’s no onscreen explanation for why Channard has the support of Leviathan to go killing Pinhead and his friends, but that’s what he does, and this is where Hellbound falls apart.

Now that Channard is a direct antagonist, Pinhead and Pals are, once again, cast in more helpful roles, but the film attempts to soften them this time and completely spoils their lore. Through flashbacks that Kirsty experiences, she learns about who Pinhead was before he became a Cenobite, which is fine, but the film treats this person as an innocent victim under a Cenobite layer, locked behind a wall of blocked memories. Kirsty reminds them of who they once were, and the Cenobites decide to defend her from Channard, who dispenses with the originals rather easily.

Like Hellraiser, Hellbound’s last ten minutes fit a more standard horror film but entirely clash with both deeper lore and things the audience saw only moments ago. The whole point of even the more complex lore of the puzzle box is that the people using it want what it’s going to give them. They’re not unwilling conscripts or innocent victims eventually twisted. This is a critical part of what makes the Cenobites unique. Then there’s the idea that they’ve forgotten whom they were, which one could argue as a fair possibility had Channard not just undergone the change ten minutes prior and manage to remember everything. It isn’t even necessary to motivate the conflict, as the older Cenobites could simply not approve of Channard’s approach or disregard for the rules in still pursuing Tiffany, the troubled girl tricked into opening the box.

It’s the classic, “there’s still good in you” bit except that goes in a different movie. You can tell, because none of it fits here without entirely disregarding established rules and prior scenes in the same damn film. It’s only going to get much, much worse from here.

Such Sights

Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth was released a mere four years later, but that may well have been a decade in 90s years. While the previous two were largely good movies that succumbed to perceived necessity with their shitty endings, Hell on Earth is an aggressive clusterlove of early 90s horror tropes and the results are mostly astonishing garbage that occasionally veers into entertaining novelty territory.

It continues, in a way, from where Hellbound left off, following the Pinhead Pillar as it is sold to a degenerate club owner, who is then tricked into releasing its gooey Pinhead centre. This works against what little the film has going for it, though, as it continues the unravelling of the lore, as this Pinhead is an even eviler Pinhead who wants to take over our realm. It’s full of the era’s worst hacky cliches, which come to the fore as Pinhead chases the main character across a city. Where basic intent once created a logical limitation to Pinhead’s “powers”, here, explosions burst from manholes and chains launch from drains, all missing their targets and forcing the problematic question of why that would ever happen onto the audience. A lot of the ghost/demon powers used in movies operate on vague inculcated rules that are rarely explicitly stated within a movie. Part of making this work is to not overdo it, because if the evil entity can just explode your head at will, the entire conflict structure of the plot is broken. Hell on Earth unthinkingly blunders into these issues constantly, which is how we wind up with the film’s best and worst feature: the Cenofriends.

I mentioned before about the iconic and how it’s a key to good horror. Talentless people know this, even if only on an instinctual level, and this will cause the braver among them to attempt to imitate it. Someone saw Pinhead, realised that was actually two words stuck together, and figured out that you could change the first word and get something equally threatening. This is how we get Camerahead, a Cenobite who looks like Danny Trejo crossed with Videodrome.

There are probably 3 separate A24 films in production about our era’s omnipresent cameras, streaming, and a demonic entity with a camera in its head, but this movie is from 1992 so it’s about a manual zoom that pokes you with the ferocity of a drowsy erection. This is all he does. He doesn’t suck you into a video world of his mind and edit you to pieces or anything remotely creative. He holds a guy’s shoulders and bugs his eye out like the horny cartoon wolf seeing a stripper. It looks like a steampunk pop-up book and is the 90s equivalent of dropping your phone on your face in bed. This is treated as something scary, and not something one of those self-proclaimed “cyborgs” would do to themselves before dying of infection.

Butterball’s deal was looking like a flaccid penis crossed with Bruce Willis but making his middle-aged demonbetes look scary amidst pins, tracheotomies, and dentistry. He did this through calm presence, a kind of confidence that comes from being staggeringly out of place, yet so confident in your position that the resulting cognitive dissonance imparts a fearsome command presence. Barbie is Butterball’s awkward twenties. A period of personality affectations that change month to month, where different hobbies and accoutrements were thrown at a wall in the hopes that what stuck would be an identity.

There’s an attempt at thematic connection with the Cenofriends and their past selves that doesn’t fit the lore and makes them feel like Masters of the Universe toys that were finally rejected for being too dangerous for 8-year-olds. Pinhead didn’t collect butterflies, but Barbie the Bartenderbite comes with everything you see here. Fill him with rubbing alcohol and whatever you do don’t use him to set your little brother on fire. If you find yourself asking, “how do we turn bartending into a demonic threat?” the answer is, “you don’t” now move along.

From the same unmonitored child that gave us Camerahead, we get Pistonhead! Wow, look at this guy. What a wild looking dude. I bet he disregards the rules at school. He’s horny. He’s the Poochy of Cenobites.

I hate Pistonhead so much that if I were to be turned into a Cenobite, Leviathan would make me Pistonheadhead and my head would be stuffed with a bunch of tiny Pistonheads. Feet first so they could constantly talk amongst themselves about how boobs rule.

The last thing your scary monster is supposed to elicit in a viewer is crushing pity, and yet that’s what we get with CD, the Cenobite who throws CDs at you. Even his portraits make him look like a goober stepdad desperately trying to connect with the stepchild who hates him for no good reason.

He dispenses CDs from his tummy to throw at you, meaning the one in his mouth that makes him look like Kermit when another Muppet zinged him is just there for him to suck on. The leather thing on his face that looks like a covid mask worn by an anti-vax dominatrix is even described in his wiki entry as being there just to hold the CDs in.

He has the kind of face where you know he wants to talk to you about his Laserdisc collection, is polite enough to sit in creepy silence until the subject comes up naturally, and is stupid enough to think that will actually occur. Other Cenobites lie about weekend plans to him and leave his messages on read. Nothing about him is cool or threatening and I’ve actually been cut by a thrown CD. Thinking about him makes me sad, and the ability to unwittingly cause a form of suffering unavailable to butcher’s knives is the only reason the other Cenobites pretend to be his friend.

Mattel Presents: Hellraiser 3 has novel moments, but even the good bits aren’t the right bits. There have been many off-brand Cenobites over the years, but none as lucky-dip shit as these. About the only way they'd work is if you went all-in and made a Saturday morning cartoon with them a-la Toxic Avenger. Hell, I'd buy the action figures. But that's this film in a nutshell. It has the feel of a self-aware, meta sequel from 30 years later, but without the irony that makes you laugh with it instead of at it, meaning the latter is really all it’s good for.

I am so exquisitely empty.

The last one that connects to the original story is Hellraiser IV: Bloodline, which is the one I always forget exists even though it features giant space origami. The goal of this one was to do a story that covered three timelines spanning generations of the LeMarchand family—beginning with the man responsible for first building the puzzle box, a modern-day architect, and ending with an orbital engineer—and the script was, by all reports, reasonably good. What happened to it is a tragedy of studio interference, cutting the budget here, insisting on more Adam Scott there, and the result is a mixture of the weak and the silly directed by the official Director’s Guild “this is shit” nom de plume, Alan Smithee.

It has its moments, unsurprisingly coming from Pinhead’s solid lines, including one about pain where he is simply offended that a human would use that word with him as though they could know it and love it as much as he does. This basic concept, that pain is a glorious, loving joy, is the kind of third scary thing, the truly alien other, that can exist as both basically terrifying in a material sense and disturbing in an intellectual one. That said, it continues the problem of overexplaining the Cenobites, adding a princess and some lines about power struggles in hell. It’s all too close to the dully predictable pieces of western religion a lot of horror films deal in, and the rest of the film just isn’t enough to carry it. But hey, at least it’s none of the next 5 films.

And I will enjoy making you enjoy it.

The next four movies are an unofficial “other movies with Pinhead added” quadrilogy (though there is debate about that with Inferno). Each is effectively its own standalone story with a Pinhead cameo around the end and each follows a nearly identical pattern of unreliable reality. The most successful of these is the first, Scott Derrickson’s Hellraiser: Inferno, about a detective chasing a killer through a questionable reality because the killer turns out to be him and he’s already in hell. The standalone elements of the story are okay, and the execution isn’t bad, but this is the first concrete time where Pinhead is a demon whose job is to punish sinners.

Which sins? Things like this are easy to brush past when the sinner in question was murdering children, but is Pinhead going to rip my skin off for wearing mixed fabrics? Is it only mortal sins? Commandments? What if Pinhead is Mormon? Beyond contravening established canon and forcing a variety of stupid questions, it kills the thing that made the Cenobites interesting in the first place. There is no more mystery, no more allure of pain and pleasure intertwined. His neat design can’t hide the fact that, as of Hellraiser: Inferno, Pinhead is no different from a guy in a red devil onesie, poking people for being jerks.

Hellraiser: Hellseeker is about a guy chasing the killer of his girlfriend through a questionable reality because the killer turns out to be his girlfriend and he’s already dead and in hell, because she made a deal with Pinhead to trade his soul, along with the souls of some otherwise innocent girls he was cheating with, for hers. Also, the girlfriend is Kirsty from the first two movies, in a role reduced to what amounts to a cameo, so the story can focus on her boyfriend, Dean Winters, attempting to look confused for 89 minutes.

Having the story of this film be about Kirsty dealing with Pinhead to get revenge, only to turn that into a reveal and instead focus on Winters being startled by jumpcuts amounts to narrative malpractice. The film is structured like the Warner Bros cartoon Duck Amuck but starring a plank with a face-like knot. Winters gets confused by a horror scene, an edit makes the horror things go away, confusing him, all to suggest a greater mystery he is far too confused to solve. Winters has the natural likability of childhood leukaemia and the face of a Mickey Rourke stunt prosthetic. Watching this thing crinkle into one of three angrily baffled expressions while edits happen around him is something I could experience by asking my housemate to explain Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure to me again. Making a movie of it only adds the insult of the biggest waste of a major character since they killed Michael Biehn off at the start of Alien 3. Pinhead and some other, off-brand Cenobites show up for a few minutes in the final act to put an end to things, making this the third time they’re technically heroes. This is a tie for worst of the franchise and I fucking hate it.

The next two, Hellraiser: Deader and Hellraiser: Hellworld are an odd little pair. They were both made in Romania in the same year, which should give you an idea of what to expect, and both have the distinct aesthetic you get when you give a first generation affordable high-def camera to an Eastern European skilled only in defrauding Soviet governments. A lack of colour balancing for the HD means the grey haze of sadness that permeates the former Soviet states is visible in all external shots, and the camera moves with the childish enthusiasm of someone using every angle and effect as they come up in the textbook. The results look so much like a mishmash of PS2 cutscenes, leftover Blade dailies, and Steven Segal power fantasies that I kept expecting Milla Jovovich to pop up.

The first is certainly the better of the pair and is about a journalist chasing a story through a questionable reality before she is killed and reanimated by a guy using puzzle box energy to create a disaffected youth sad enough to properly open it. Knowing she is already dead, the journalist opens the box to let Pinhead kill the pouting eurotrash, before she slits her own throat to avoid going with him. Like the previous instalments, this is a standalone film with a Hellraiser coat of paint, so Pinhead only shows up at the end to pose and throw some chains around which winds up a detriment both to the franchise and the movie its parasitised.

The film is serviceable, the lead isn’t bad, and it actually structures its reality intrusions to properly escalate them into something that would pay off, were any real relationship between the narrative and Pinhead’s presence in it. A messianic cult figure using an object to reanimate the dead on a quest for power is a round hole the puzzle box and Cenobites’ square peg doesn’t quite fit in. Deader’s competent execution creates a decent air of mystery the Hellraiser franchise insertion completely ruins, while the plot’s clear lack of connection to the lore leaves the Cenobite appearance at the end more a fanfiction cameo than sensible conclusion. The result is not offensively bad, nor particularly good, and entirely forgettable as a result.

Then there’s Hellworld. If Deader were the object of desire, Hellworld was the price to be paid.

Hellraiser: Hellworld exists as its own puzzle box to hell. It opens a door to the labyrinth of Romanian film laws and reminds me of Jay Leno. See, lots of entertainment contracts are pay for play, meaning you get paid only if the show is on. Leno, when he was kicking and screaming over The Tonight Show, had a pay and play contract, an insane thing where NBC was literally forced to air his show or be in breach. Countries with cheap filming locations and industries often protect/pay lip service to the local industry by having laws that force big international productions to help said locals out, usually by hiring a percentage of local talent. Romania’s baffling package deal somehow mandated a second film be made, which is like building an open-air public toilet in your backyard to get your dream house built when your dream house is one giant verandah. It would have been better to simply pay a bunch of Romanians to do nothing. It was written in a fortnight, filmed in three months, and it shows.

There are people who defend Hellworld, but there are people who defend rampant polio and being beaten as a child, so it’s worth remembering that time has a way of making you forget all the iron lungs. This is a film that forced itself upon its creators, a non-consensual act whose victims fought back with every limp cliché the two-thousands had sitting around, from trite meta and MMO references to the Nokia 3210 and Lance Henriksen. The eponymous Hellworld is a massively multiplayer online role-playing game according to people who have no idea what those games look like, and a group of teen players loses a friend to suicide after he gets a bit too into it. Years later, the remaining teens get a ticket to a game themed party at Lance Henriksen’s mansion by playing it in the worst display of filmed gameplay since the olden days of joystick semaphore.

As dipshit ridiculous an idea as Pinhead stalking you through a slightly less desperately horny World of Warcraft would be, it would at least have had the chance to be stupid in a fun way. Instead Hellworld’s MMO component exists only to smear a blood flecked skidmark of dated cringe onto the film, as it could have been replaced with anything and is functionally irrelevant after two minutes anyway. The teens wander a europarty of dubious reality, dying in only moderately interesting ways, until it turns out they’re all hallucinating in coffins after Lance—the father of the dead teen who blames the others for his obsession—dosed them with LSD and other drugs that absolutely don’t work like that. Pinhead shows up in what amounts to a post-credits scene to kill Lance, after the latter solves the actually real puzzle box his kid had found.

The producers of Law and Order: SVU couldn’t have made something worse if they teamed up with Southern Baptists for an educational video on the dangers of Dungeons and Dragons, but the rest of the filmmaking is too functionally competent to let Hellworld be so bad it’s good. Nobody’s clumsily acting through the film only because they’re the friend of the guy who made it. There’re no visible wires or quaint, handmade effects. It's professionally made, but with the kind of menu-item functionality of a music video for a label-made poser group. This grinds the possibility of anything interesting out of it, leaving you with unremarkable gore and a twist ending a horror-writing algorithm would reject. It doesn’t suck because it’s the most they could do; it sucks because it’s the most they could be bothered doing. It ties Hellseeker for worst of the series, a dull yin to the former’s offensive yang.

The counterexample to Hellworld is actually its sequel. Hellraiser: Revelations is the 9th of the series and was unashamedly made over a fortnight with no budget simply to maintain the rights. A daytime soap set, whichever actors on that soap who secretly live in the studio for a cast, a guy who looks like Bobby Moynihan as Pinhead, a runtime of 75 minutes, and a budget of go fuck yourself are the kinds of legitimate challenges that make the resulting movie an actual accomplishment and perfectly illustrate the core elements of “so bad it’s good”.

There’s an ironic reappropriation at the core of the “so bad it’s good” concept. A kind of homicide of the author that inverts judgement by imposing an entirely opposite set of criteria. For this to function, the work in question needs to be honest. The comedy of works like The Room comes from the space between the intended meaning and the received meaning being yawning enough a chasm to stand out as absurd. Revelations has nothing, but tries. That’s its core of honesty. Hellworld had everything and didn’t try. This is the difference between enjoyable shit and shit.

There’s a point around the end of Revelations where you’re watching Bobbyhead wandering around a soft-focus soap set, ripping the skin from the weathered but still beautiful milfs and dilfs that populate those worlds, and you realise you’re watching an episode of Passions where Tabitha decided to cut the shit and call in a favour from Leviathan.

The tiny sets, whose necessitated close-up shots reveal the very falseness they’re trying to hide, mesh with the competently delivered terror from the actors to emphasise the incongruity of what we’re witnessing. It lends a genuine quality of surprise to these reactions that better actors lose amidst the competently built tension that comes with vastly superior production values. Nothing communicates the idea that He is not meant to be Here inherent to the Cenobites more than a total clash in tone. It’s the “Pinhead in Warcraft” that Hellworld was missing, and to top it all off, they actually get the character right. He’s not punishing shit, he’s here to collect a demented little fuckbag wearing his friend’s skin after a pleasure trip to Mexico.

It’s like that episode of Sabrina the Teenage Witch where Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa guest starred as Shang Tsung but if he were actually performing fatalities, and if you don’t want to watch that then why the hell are you here?

The last of the ever looser “original canon” is the largely okay Hellraiser: Judgement, a film made by people who genuinely wanted to make it and with at least enough of a budget to look better than Revelations. If the previous entries were body horror, then Revelations is glandular horror. Blood still dominates, but with it is a distinct layer of salivary clear ooze that’s admirably grotesque but whose closeness to disgust over pain makes it feel out of place. It works in this piece like a signature, which is for the best as the plot veers closely to a rehash of Inferno and the lore cements itself as blandly Abrahamic.

Once again, the cop searching for a serial killer through an occasionally questionable reality is the serial killer, but this time one tasked with this by angels from god, with the goal of inspiring fear in mortals again. The cop/killer finds a puzzle box, leading to an interdepartmental conflict between Pinhead and some angels, resulting in Pinhead slaughtering one and being banished to Earth as a mortal for punishment. The best bit about this film is actually a new character, The Adjudicator, one of hell’s minor bureaucrats (played by the film’s director). He has similar mannerisms to Kryten from Red Dwarf and is emblematic of how even the dull concepts of this film are helped over the line by creativity of execution.

It's a bold attempt, with certainly more care than its predecessors, and manages to be a fun enough film on its own, but it is dragged down by a tired plot and a headfirst commitment to the exact things that ruin the lore and character.

Two minutes. Two centuries. It all ticks by so quickly

Hellraiser (2022) has the advantages of being made in a time with easy access to both audiences and the kinds of production values prior entries couldn’t have dreamed of. It’s also a reboot, which you can tell because it doesn’t bother with a subtitle. This was certainly a better idea than sticking with even the vague continuity of the original series as it allows for the kinds of fundamental changes necessary to, if not do it right, at least do it with a sense of creative cohesion that being used as a franchise reskin on an unrelated script naturally thwarts. It does do a lot of the basics right, and is a fine enough film, but is ultimately emblematic of the pitfalls around the concept.

There are two things it improves that deserve mention, even though it doesn’t really use them. The first is the different stages of the box relating to different desires. This is a necessary step to unshackle the series from its horny roots. Not that those are bad, but that level of horny is hard to sell as sympathetic to an audience and the word “desire” does have broader meaning that should be respected. Power and sensation can easily skew villainous, but life and knowledge are easy things to be seduced into desiring, and thus perfect for Cenobites. While I do like the structural approach of 2022, opening desire up to even broader meanings allows for a much wider net of sympathetic victims which has been one of the series’ sticking points. Again, the movie doesn’t actually do anything with this, but it’s a worthy addition to the concept.

The second good addition is a thematic shift from hedonism to addiction. Addiction is sibling to hedonism, fits Pinhead’s pusher-like attempts at corrupting anyone they don’t have cause to take, and is the kind of thing you can use to drive the movie without adding extra moving parts. An addict’s behaviour can drive a horror plot in ways that are internally consistent and sympathetic, removing the ugly clutter of stupid characters or extra plot devices. A victim who pursues their own torment while chased by caring innocents makes for a perfect Hellraiser film. But this idea is left more a sub-plot that evaporates before the halfway point which leaves the film falling over itself to fix problems it already has the perfect solution for. Instead, the film makes a fundamental change in how the puzzle box works and it is not for the better.

Like the rest of the lore, LeMarchand's box is another thing that’s more challenging to write to than it appears. It’s a great piece of design and a wonderful prop, but there’s simply no connection between solving a puzzle and wanting your skin ripped off. I like to fidget with puzzles, this shouldn’t mark me down as irreparably horny. The puzzle box as a trap would fit a villainous monster who tortured the innocent, but that’s not the Cenobites. This innate complication had to be addressed in Hellbound with the line about desire being what really summons them, and other media has added details about the box magically selecting people to support this, all so the audience isn’t left thinking that if solving a puzzle box summons the Cenobites then Hell must be filled with confused Autistics.

2022 makes the box eject a little blade when a piece is solved, with whoever gets stuck being yoinked by hooks whether they want to or not. Now, the innocent can easily be marked, as is what happens with Riley’s brother Matt, but it also makes it officially a matter of hands over desire. Without this desire, and without the ability for the Cenobites to make any decisions regarding that, they become mere tools of the box with as much character as the little blade. The old quote about being explorers is there, but it’s meaningless because there’s no actual character behind it. They aren’t proselytising a belief that indicates a frighteningly alien perspective, they just take whoever was stabbed. A point which hits its absurd zenith when Chatterer is stabbed with the box and then explodes for some reason. Why? How come Pinhead didn’t rip him up with the hooks? And where did Chatterer go? Bonus Hell?

This change also largely invalidates the plot.

It’s revealed that Riley’s sorta-boyfriend Trevor was working for Voight, with the whole relationship and theft being a ploy to get her to open the box. Had the desire component remained, this convoluted nonsense would have some internal logic related to manipulating her into willing it herself, but if you can just stab people with it, which happens, then why go to any of this trouble? If I desperately wanted a baroque harp pulled out of my chest, I’d hardly be giving my troubled youth a task that involved a monthlong seduction. Just stab 8 homeless people with it and bingo! Wishes for all. It’s a staggeringly unnecessary twist in the first place, but with the changes made to the box it just fucks up the plot.

The production values and care are there to make this more than watchable. The spatial warping is finally done justice, which also leads to another great moment involving a larynx, but the plot has clumsy gaps, and the Cenobites have no character. It’s just another example of how even genuine effort can be thwarted when the complexities of the core idea aren’t fully understood.

Allow me to show it to you.

I’ve lived long enough to see things once deemed unfilmable become massively successful film franchises, so the good news is that Hellraiser is a difficult task but not an impossible one. It’s really a matter of keeping a few things in mind:

- The Cenobites are characters, not monsters.

- They love what they do and think other people will enjoy it too.

- While they have rules and internal logic, the less explained the better.

- Don’t make them part of any religion.

Another important part that is more to do with the underlying structure of horror films is that a Hellraiser film needs to be an intense body horror experience. A persistent flaw all but the first two films had (usually as a side-effect of being entirely different films) was structuring their violence escalation on the traditional 0-10 scale (Judgement differed but went more toward disgust which isn’t the right feeling), and this clashes with the concept of the Cenobites. Pinhead is clearly seen in the opening moments of Hellraiser and Frank’s/Julia’s rebirth scenes are nightmare inducing works of practical effects that take place around twenty minutes into their respective films. The Cenobites are proud preachers of a way they consider beautiful. They do not hide in shadows because as terrifying as their appearances are, they are nothing compared to the pleasures that await. A Hellraiser film must start at 10 and escalate from there. Experiences of an intensity that shock and linger are written into the concept’s DNA. The idea that any film in this series would deny viewers the sight of an ornate golden nerve-twister being installed is sacrilege. They have such sights, so fucking show them.

With these rules in mind, a roadmap emerges.

To begin with, I’d go with an ensemble approach over focal protagonist as this will mirror well with the Cenobites themselves and create a substructure that promotes character moments for both sides. There’s nothing inherently wrong with the other approach, but the aim here is to emphasise Cenobite character, which even the better movies haven't done outside of Pinhead. I’d modify the precise function of the Lament Configuration to be a desk bell over an ironclad contract, where it summons the Cenobites, but you can still refuse them. It will also tease the solver with psychic visions of what joys they can expect at different points of the puzzle, so one has to be consumed with a dark curiosity to continue. A similar kind of idea exists in the expanded canon of the earlier films, but it’s in the somewhat magical fate way the box finds people in the first place. This way is cleaner, filters out innocent puzzle enthusiasts, allows for the more seductive side of the Cenobites to show, and means that people who ring the bell are at least a little Ceno-curious.

The narrative would be a group following a recently relapsed opiate addict friend into the Labyrinth, with the goal of getting him/her and getting out. Making it a relapse after years of sobriety will emphasise the tragic aspect of it while providing a genuine reason to believe that they can be saved, validating what could be otherwise perceived as stupidly dangerous behaviours. Setting it mostly in the Labyrinth allows for a lot of narrative shortcuts which will leave more time for character and gore. The Cenobites would function more like a body-horror Goblin King, not helping or hindering precisely, but motivated by their own goal to expose the cast to more of their world, believing that to be the key to gaining their consent. The Cenobites don’t control the Labyrinth, so it can contain independently functioning threats, like The Engineer, and even other stray humans. This way, the film can have the kinds of active menace a horror needs and some extra set-piece victims, while keeping the seductive background menace of the Cenobites pure.

That menace ultimately stems from the Cenobites being horrifying entities who could do any number of deeply terrifying things to you but aren’t. That space between capacity and execution is character, and when the execution is something so vile, a deep menace will take root. The plot specifics after this are relatively flexible, but it’s important to maintain the threat as being that this place and these beings exist at all, and that they are so certain that you want to go with them that it leaves you wondering. Keeping that seductive menace intact is something the first film failed to do which was its fatal flaw, so maintaining this is critical.

After that, just think of the last pain you’d want to experience and put it in the first act.

This area’s reserved for surgery and mentally disturbed patients.

When your goal is to make something that frightens, disturbs, and upsets people, making money with it can be a challenge. This problem is multiplied when your something requires expensive special effects to be realised, because now investors will be trying to predict whether it will be profitable or not before a single shot is allowed to be filmed. Couple this with the necessity of a cinema release and selling your film to distributors, and it’s a miracle anything got released at all.

The last decade has seen a convergence of the vast audiences accessed via the internet and affordable quality special effects, finally creating the environment for a horror renaissance. There are the expected original works erupting out of this, but also a surprising number of solid remakes or sequels to dormant franchises being released. Each allowing for a new approach to an old mask, adding one thing or refining another, and I hope Hellraiser continues in this fashion.

It's a long running series, even though the Cenobites’ fame pales when compared to Jason or Freddy, because the concept’s depth speaks to us, even when the film fails to. Some are certainly worth watching. Parts one and two proudly define the series, three and nine can be funny, while ten and eleven fall short but certainly try. Each will tease you with possibility and tickle a strange, sometimes denied desire for more, evoking what lurks at the core of the concept. An alluring mix of the impossibly contradictory that draws us in and confounds us, not unlike an ornate puzzle box.

By Gabehead.

Comment on Raising Hell

To reply, please Log in