Describe one sitcom dad and you’ve largely described all of them. They’re snowmen, crafted to be observably humanoid by people who either lack the time, talent, or audience to manage creativity beyond balls of decreasing size. Each is adorned with a few chosen items to make it stand out, but whose pool of possible items is so homogenous that they wind up blurring together anyway. A blue-collar job here, a Patrick Duffy there, still just 3 balls of decreasing size. The rest of his accompanying snow-family similarly stand out only because their stacks of spheres are smaller. They’re not characters and they don’t grow, just melt, only to be rebuilt next year with a slightly different arrangement of generic items.

The Simpsons began this way, but one of the ways it distinguished itself was by using the safety-net of animation to create depth via the sitcom antithesis: genuine pain.

Homer is a generic, middle white dad with interchangeable hobbies like fishing and homophobia, but his stupid selfishness becomes more than an adorned snowball when we see the painful insecurity behind it. Episodes like I Married Marge show us that he knows he’s too stupid to solve his problems, episodes like Dead Putting Society show how that pain manifests his oafish need to feel like a winner, and episodes like When Flanders Failed show us how these elements meaningfully interact to make a complex truth of the generic kindness expected of his role.

Marge is a sitcom mother, little more than sockets for eyes to roll in because a writing room of 90s guys can’t even think of the female equivalent to her husband’s generic hobbies. Like most shows, they try to trade this off by making her smarter than her husband, but that only makes her seem all the stupider in her inexplicable tolerance. Unlike her husband, Marge’s pain is dangerous to her narrative world because it demands action she is smart enough to be expected to take. But episodes like Moaning Lisa showed us that, unlike her husband, Marge has an inner self her life has built walls around, and episodes like Life on the Fast Lane showed us that decisions are made behind that wall. Decisions we may not understand, or agree with, but not the inexplicable patience of a tolerant fool.

The precociously intelligent child is not an archetype unique to The Simpsons, but Lisa’s particular form of it was. She shares a dangerous level of intelligence with her mother but lacks the walls the series uses to vent the logic remainders that intelligence creates. Instead, she gets actual serialisation, albeit one compressed into a safely containable form by her youth. What results is more a character than archetype, even if these characteristics are stereotypical, because they’re the experienced results of her conscious responses to her actually changing world.

Then there’s Bart.

Bart is at the centre of a prism of forces that limit him more than any other family member. His anytown retro basis thwarts identifying markers that would put him in a time-appropriate subculture or otherwise grant him some proxy personality. He loves his skateboard but has none of the identifying features of a skater. His toys are generic floor clutter. His idol is an in-universe clown, an idea that was 30 years out of date when the show first aired. His comic role simultaneously needs him to be as dumb as his father but without the full life that gives Homer his depth; as smart as his sister to outwit his authority figure foils, but without the ability to turn any realisations into a serialised personality; and he can’t have his mother’s inner self because his self-ignorance is used as a buffer for his narratively convenient selfish acts. There’s no description of Bart that doesn’t sound like what a marketing team and a whiteboard would come up with if the prompt were “ten-year-old boy”. What’s left are smatterings like his beauty pageant tips, a nearly imperceptible sub-structure that borders on fan canon.

New Kid on the Block was an episode specifically requested by Jim Brooks to introduce new characters and subsequently foisted upon Conan O’Brien, a fact which shows in the results. There are ways to do this story, but when you don’t really care, you’ll go with the template, even if it doesn’t fit.

Bart’s sub-personality is a combination of genuine alienation and the affected coping mechanisms that this alienation develops when left untreated. Getting even childish infatuation across this line is difficult when your character is a walking clump of oppositional defiance who hates good things on principle, and that’s ignoring the other complication of this episode. When Bart’s friend fell in love in Bart’s Friend falls in Love, Bart’s third wheel status meant there was no need to validate the relationship to external viewers. This time, the feelings are Bart’s, so the audience needs to see the why of the infatuation to bond to his emotional perspective. It’s no easy task, but one the episode nails in the character of Laura.

She’s somewhere between 13-15 (can’t find a clear age anywhere), making her naturally more mature than Bart, and had a rebellious military brat childhood and broken home, which has given her a mix of naturally mature characteristics and the confidence to push those further. The short runtime means there’s a real chance this confidence could present as naïve, but for a perfectly cast Sarah Gilbert.

Gilbert was 5 years into Roseanne, which had spent its run thus far as one of the top three shows in the US, so her casting as a genuinely mature girl whose life experiences gave her every reason to be confident in that maturity was a natural fit. She was also 17, meaning she didn’t need to affect any kind of younger voice. Both elements combine to give Laura the kind of effortless realism her role requires. Clearly more mature than Bart, and mature still for her presented age, but child enough to make Bart’s interest plausible. She enters the episode picking up on one of Bart’s pranks, claiming it, expanding on it, and turning it back on him. She knows the tricks he’s going to pull before he does, and she pulls tricks he doesn’t know on him. She bullies the bullies. The result is a character whose every onscreen moment is a perfect demonstration of why Bart would be immediately taken by her. It’s a well-executed narrative hinge but it’s let down by the rest of the story.

There are a variety of ways to enact a story about infatuation, with Bart’s age closing off many and Laura’s age closing off the rest. A fuck-based adult relationship and child’s asexual puppy-love story will be structurally identical, even a post pubescent age difference will just be the standard “love obstacle”, but the fundamental difference between pre and post-pubescent human means the infatuation will be entirely one-sided. There is no relevant response for the object of the crush, these stories are about how the subject deals with these feelings when they’re new and the barrier is truly insurmountable. As such, this can only be a story about Bart’s maturation.

On the surface, this may seem impossible. Bart is a child with no history, an idiot with no serialisation, and a self-ignorant brat in a story that demands introspection and growth. But then there’s that developing substructure. The Bart of season four is not the same Bart that sobbed at Krabappel’s desk when he failed a history test in season two. Having calcified into America’s Bad Boy™, it would be almost impossible to even imagine such genuine vulnerability. So, something is changing.

The thing about his prism is that, as static as it can appear, it must shift. The smart must make way for the dumb, the child for the edgy teenager, the shallow for the deep. He can do this because he doesn’t have the burdensome history of his father, his sister’s intelligent self-awareness, or the binding agent of his mother’s inner life. The forces that crush him can only act one at a time, meaning Bart’s prison constantly changes shape. The surface these shifting forces creates is two-dimensional but can fold over itself to give the illusion of depth. It’s by no means deliberate and its illusory nature confines it to this specific type of sitcom, but it does function as the missing depth Bart’s family possess.

Well, at least it would have if the rest of the story had been written properly.

As mentioned earlier, this wasn’t a story someone wanted to write, but one they were forced to write, and the result is some staggering narrative sloppiness and an incredibly dumb conclusion.

This love story isn’t a love story, Laura’s not even aware there’s a crush happening until her final line, it’s a personal growth story crammed into a love story structure. The result is a total absence of necessary character moments for Bart. Just eight episodes ago, Bart was treating Milhouse like a mutant for his interest in Samantha and now he’s doing the exact same thing. He showed no internal discovery, debate, or self-loathing, no recognition that there had been a different state at all. It doesn’t even need serialised information, it’s acknowledged that this is Bart’s first crush, but that’s ignored for an awkward pair of love obstacles.

The love obstacle in a romance is anything keeping the protagonist from their paramour. As odd as it can sound, “not being noticed” is a fairly common one, with entire genres of romance fiction basically amounting to a girl finagling her way out of the friend-zone. As these narratives predicate themselves on the target realising their love for the protagonist, the form has a lot of room to move. A character can grow into someone the target will love, the target can realise that their true love was right in front of them all along, or any blend of the two. The one-sided version of this that ends in educational heartbreak is what Bart would be going through here, had there been any character moments. Instead, it’s pointless motions rendered even more meaningless by a late shift to another love obstacle.

The love rival is one of the cruder plot devices in all of literature because there is no inherent villainy in also having honest feelings for someone, yet the need to overcome them will inevitably position them as antagonists. With their only crime being “not the protagonist” the love rival became a dumping ground of character faults, that gradually grew to absurd villainy, to ensure the protagonist could do what the narrative needs without looking like a selfish maniac. It’s base, but it’s also a very simple device to use which makes this episode’s misuse of it an achievement.

The idea is that the love rival is revealed to be the bad person the protagonist knows they are, and the audience has seen them to be. She runs a stray cat clinic, and he secretly runs a cat kicking league. There has to be an obvious poetry to this, if he runs a cat kicking league then he can’t be arrested for unrelated embezzling. The narrative loop needs to be closed for there to be any payoff and to keep the protagonist a meaningful agent in their own plot.

Jimbo is a great choice of love obstacle because the audience already knows him as a bully and a jerk, but aside from this there is nothing done to forge a meaningful connection to his eventual comeuppance. The girls feel he’s a good-looking rebel who plays by his own rules, but that’s broad to the point of meaninglessness. Had the ending involved his mother arriving to yell at him and Jimbo being revealed to be a huge mama’s boy, there would be some connection. What we wind up getting is some last-minute deus ex Moechina and the commentary’s admission that it was stupid.

The irritating thing is that there was a setup point that would have fixed this earlier in the story. When the discussion about the body behind the mayor’s house came up, it could have been mentioned that Jimbo was bragging about how he wasn't scared of a body because he wasn’t scared of anything. He could emphasise that he’s a mighty 6th grader who would never cry at something scary like a wimpy 10-year-old kid would, even a knife-wielding maniac. This is a setup that validates the conclusion. Being menaced by a deranged Moe armed with a machete would be enough to make adults cry. This is akin to our evil love rival being mutilated by an as yet entirely unseen Michael Myers in the closing 5 minutes of the film.

Like a lot of the classic period, the faults exist around a lot of otherwise good to great work. The Frying Dutchman story is fine comic goofery by itself, but it interacts cleverly with the main plot via Homer’s court time requiring Laura to babysit. Attempting to perfectly integrate plots is difficult and defeats the point of a B in the first place, but little things like this or Bart asking Lisa for help because he couldn’t understand Homer’s expanded vocabulary in Bart’s Friend Falls in Love provide a sense of meaningful coherent reality for very little effort.

Then there’s the fact that Laura and Ruth work as well as they do, given they were mandated. They are fine additions to Springfield who are sadly consigned to the junkheap of background characters almost immediately. Casting a noticeable celebrity voice as Laura was a critical mistake here, but abandoning Ruth is a sadder waste. She has one solid turn in Marge on the Lam before being forgotten until a minor role in Strong Arms of the Ma a whole decade later.

The Simpsons is an historical hinge point between the cartoons of yesteryear and modern animation, making some of the case studies it presents truly unique. Many other series mix the absurdly cartoony with serious depth, but even examples that deal in surprising pathos, like Adventure Time, do so via serialisation. Why wouldn’t you? It makes most of this simple and who can’t catch up on a show these days? It’s so obvious that it makes a character like Bart, a thin scrapbook of non-copyright stickers that say “radical”, something truly unique. His depth exists like anti-matter, something we can’t directly observe but can only conclude exists through careful observation and esoteric mathematics.

New Kid on the Block had one primary job to do, introduce Ruth and Laura, and it did that tremendously. Their subsequent abandonment is a crime to be laid at someone else’s feet, but the lack of real interest here shows. Elements were hastily grabbed and assembled into a patchwork that shifts targets when it looks like its failing only to have already missed the new selection. It teaches us nothing about love and nothing about Bart, but in doing so gives us a peek at something fascinating in the darkest reaches of his universe.

Yours in driving around until 3am looking for another all you can eat fish restaurant, Gabriel.

The First Annual Gabriel Morton Award for Outstanding Achievements in the Field of Simpsonness.

Best Line

This episode isn’t one for legendary lines, as a lot of the stand-outs are of the very dry type that fall into regular use but for their function more than their referential utility. The rest were usually bound up in deliveries and moments so much that they were needing to be categorised as jokes as a whole.

There’s a fundamental insanity to Homer being super excited to take medicine that isn’t prescribed to him considering he isn’t a junkie. Getting this joke to land without veering into “just drinking detergent territory is a tough balancing act which is why this next one makes the list. Castellaneta’s delivery of “Maybe I’m not getting enough… estrogen” is a goodun for the pause before the perfectly pronounced and plainly delivered “estrogen”. The dry read shifts the form of stupidity away from HA HA WACKY to a more understandable thing to not know, sanding the rough edge from the gag.

The Simpsons being from an earlier era means it’s almost never as explicitly adult as later entries like Family Guy or South Park. This is what makes the next runner up stand out. Bart saying, “Here in the dark, you won’t need those eyes, let me have them!” is a level of violent imagery that’s rare for the series, that becomes funny when paired with Nancy Cartwright’s high-pitched sock puppet voice. It’s so patently silly that it took several rewatches to even notice Bart trying to rip Lisa’s eyes out and fed into his turned-up eyelid scare.

The next pair are close together and are almost two sides to the same coin. The first is in the same vein as Marge Gets a Job’s “parge the lath” and involves the use of technically correct language being used in a technically correct context. Labneh is a strained yoghurt (that is absolutely not spelled “labna” as the Frinkiac has it) used as a dip and it’s quite nice. Bart has never had labneh, so his authoritative statement “Now THAT is good labneh” has the obvious comic quality but pushing it over the edge is the word “labneh”. It’s wonderfully alien to English, LAHB-NA, and has a singsong quality to it. Like “parge” and “lath”, the gibberish quality of it is contrasted with the obviously not gibberish uses of it and results in one of those lines that sticks in the mind.

When we cut to the restaurant “Two Guys from Kabul” the scene is one beautifully loaded with story and character that absolutely didn’t need to be there. Kabuli Man 1 and Kabuli Man 2 stare intently at opposite sides of the empty restaurant, clearly to avoid seeing each other, with only the brutal ticking of the clock for company. “Sometimes I think you WANT to fail” makes the list because it’s a great example of how much you can do with a well delivered single sentence. There are lots of obvious alternatives, like “I TOLD you this wouldn’t work” or any number of similar sentiments, but the “WANT to fail” creates a long history of failures whose repetition would have to indicate desire. Things like this etch the moment into a living history that keeps it from being a pointless cutaway joke.

When Marge asks if the bread contains seafood, it’s one of those questions one already knows the answer to. Of course, the bread doesn’t contain seafood. When does bread ever contain seafood? The Frying Dutchman’s waiter says “Yes” to that question like you’re from the alternate universe that has weird, fishless bread which is what makes it so funny. Getting humour out of a single word response in the affirmative is a tricky accomplishment worth notice, and it really comes down to the delivery here. It’s a blend of the authoritative with the vacantly non-threatening, so curt as to almost cut Marge off but so simple an answer to a simple question that it couldn’t be considered a slight. It’s a form of incredibly noticeable irrelevancy that the series could produce like it were nothing.

I’ve written earlier about how the series has to use things like Marge reading Homer’s letter in the car to get Homer to express ideas by proxy when they wouldn’t sound right coming from him, and this next line uses a similar process to suggest a joke too stupid to show. Marge and Homer driving around till 3am looking for another all-you-can-eat fish restaurant is silly, but when replies, “We went fishing” when asked what they did after that, it’s a skilled application of this idea. Showing this would have been dumb to the point of impossible as it would involve seeing Marge suffer through all of it and stretch the credulity band to the point of breaking. Marge’s confession lets it exist as a perfect idea unencumbered by awkward reality. That she does it while bursting into tears in a courtroom adds an extra dash of contrarian seriousness to the bit.

But the winner is…

There’s really only been one time when I was confronted with a woman so dazzling that I’ve made an instant idiot out of myself. She was a 19-year-old Ghanian\French girl whose wild wavy hair and dazzling eyes made her look like every high-energy-dingbat anime girl I’d ever had a crush on. I can’t remember what her actual name was because she didn’t use it, she went by Jelly instead because apparently it was similar sounding. She was partway through being introduced at postwork drinks when she giggle-shouted, “I’m Jelly!” and gazed at me like a catgirl waiting for a piece of string to move.

I’d already been drinking so I wasn’t there enough to stop my brain from trying to come up with something clever. Her eyes sparkled in that way the Pentagon wishes it could harness. It went too long, microseconds but still too long. Her hair was a deranged mess that flawlessly framed her face. Something clever, come on, witty jelly wit…jelly. She was the kind of girl that had adventures happen around her. It went so long that some part of me thought it would be a good idea to make a kind of stalling noise to give the literate part of me time to think and the resulting noise sounded like Butt-Head impersonating Scatman John. Everybody saw this, and it haunts me to this day.

Bart saying “I fell on my bottom” takes first place, not just because it’s funny, but because of the harrowing accuracy of it. You’ll think that nobody would say something so deliberately embarrassingly funny. You are wrong.

Best Sight Gag

The Simpsons, by season 4, has an established level of realism that clashes with its cartoon reality and the show’s comic sensibility is constantly threatening to bring this conflict to a destructive head. Coming up with something obnoxious for Homer to be doing could easily be cartoonish in a way that erodes or at least wastes the established realism. Homer in the kiddie pool does a few things that run right up to that line but never cross it.

The hotdog is gross but not beyond a real person, he is probably naked, the wonder-white packaging pattern on the pool, the stray beers, the hat, and lastly the fact that he’s in the front yard. All of these elements are cartoonish, but each has enough foundational reality to keep them from making the scene an artificial joke. It would be so easy to exploit the cartoon and have something so overtly anti-social, so impossible in real life, because it’s a cartoon. But this is a character moment, a true one. Homer doesn’t even realise he’s doing anything wrong.

The next runner up is “DAS BUTT”, there should be an umlaut over the U to get the oo sound out of it, but it’s porno so I’ll let it slide. The idea of hardcore porno being in a welcome basket is insane. I have no idea if this was a thing that would actually happen in the US, if it’s an extremity joke on the bizarre contents of gift baskets, or what. The show’s family friendly nature precludes any harder jokes, so the resulting black VHS case with yellow lettering is burned into my mind.

Homer’s extra loose pants are a good example of how to dust off a worn premise. Even with the obvious setup, the joke gets more life via the effortless way they drop, Bart and Lisa watching them, and Homer’s overdramatic pose. The pose intensifies the absurdity while Bart and Lisa acknowledging it as happening counterpoints it with some reality. The result is a simple melody but an effective one.

The pull to reveal McAllister glaring at Homer is both a good one and a personal favourite having worked in hospitality. The malingerers who simply won’t leave are a real thing and a particularly irritating one to get rid of. The shot begins on Homer gorging, with only the purple tones of Springfield’s night and the edges of a sleeping Marge indicating it’s late. The pull reveals the upturned chairs and staff gathered, having obviously summoned The Sea Captain for advice on what to do.

Most of McAllister’s figure here is accidental, but the end result is a beautiful picture of rage. The one closed eye ads a maniacal quality to the expressive one. His neutral hands are curled a little, like he’s already squeezing an imagined throat. His body is immobile for animation reasons, but rigid with blinding hate. Just go home, go the fuck home, the place is closed, go fucking home. Still makes me chuckle.

But the winner is…

Part of the artistry of jokes in The Simpsons is the way they’re positioned and layered to create secondary pattern structures that enhance the parts of the whole. This moment is a fantastic case in point, as it occurs amidst a screamingly obvious joke. The classic warp fade tells the audience we’re in the mind, the twisted colour scheme supports the internal mental perspective, and Bart has his heart ripped out. It’s all as unreal as one moment can get.

But within this there is a tiny moment of universal realism, when Bart stands on his tippy toes to see where his heart is going. It’s something we all do; a reality is so profound as to be genetic. Humans, and even other species, will do it without even thinking about it. A real shot of a real actor may have this happen without any necessary stage directions or thought from any of the filmmakers, but that’s obviously not the case here.

It's the doomsday scenario of a crush being played out in a trauma fantasy, but even in that you need to stand a bit higher and lean a little to see where your heart has gone.

Best Joke

Part of the reason the lines and sight gags were relatively thin, is so many of them are tangled up in other elements to stand alone. What this does result in, though, is a selection of quality overall gags.

The first runner up is the moose. It’s an interesting case in referential humour because this is actually a reference to a forerunner of the modern prestige drama, Northern Exposure, that ran from 1990-1995. The music that plays during this sequence is the Northern Exposure theme (or an extremely close approximation) and the show’s opening followed a moose as it wandered about a quiet Alaskan village. This reference has largely been lost to time, despite the high regard and popularity of the show, as there is a bubble of pre-millennial material that lacks the defining otherness of prior decades and missed later series’ historical permanency granted by broader internet-based fan communities. The joke outlives the reference, though, as it is funny enough by itself that it doesn’t need viewers to be aware of Rob Morrow’s earlier works.

This is a very simple joke structure, a comedy reveal of some kind of pest animal, but the key is in the choice of moose. The joke needs to suggest that Homer’s behaviour is something particularly unique to emphasise his established character and how this would make living near him or selling a house near him comically difficult. He can’t just leave trash out and have raccoons show up. So what? That’s everybody.

The idea of a moose somewhere that isn’t Canada or the more northern US is wildly improbable without being capital-I impossible and while the size of the animal is certainly threatening, the creature’s long legs and large antlers leave it looking comically proportioned. The Northern Exposure theme is incredibly distinct, but a vague memory even for generations meaningfully exposed to it. Homer is surprised by the moose but talks to it like it’s a person when he’s telling it to get off his lawn. The moose appears placid, and ignores Mrs Winfield, but is immediately hostile to the oafish Homer. Each of these components has its own internal counterpoint, demanding the joke be read in ways it cannot be. It’s that twilight of peculiarity that makes it linger in the mind.

There are a few ways to get humour out of being mean to harmless old people. One is the Milhouse approach, which is to emphasise the fact that they don’t deserve it so much that the cruelty becomes comically absurd. The second is to have them do something that shifts them outside their untouchable bubble of harmlessness. Old Jewish Man’s sad little dance before being lead away uses a blended approach which is interesting, funny, and why it’s the next runner up.

He's clearly just an old man who’s desperate for human contact but pretending to be someone else’s grandfather is still a significant social violation. The sum of his sales pitch for swapping an actual relative for him being a funny little dance is insane, but still so sad. His “Hey-Hoo-Ha” routine being cut off by a defeated “Aww” as he’s lead away is heartbreaking, but the dead-eyed look on the face of the orderly implies this isn’t the first time this has happened.

It's okay to laugh at, incredibly funny, but you’re still going to hell.

Moe telling Barney not to steal beer while he’s gone is a classic comedy setup. It’s so obviously going to lead to Barney stealing beer that it may as well have been an exhortation to it. A simple setup-payoff bit always works a treat, but it’s the extra steps in this one that makes Barney’s heart stopping the second-place getter.

The obviousness of the setup is seemingly paid off almost immediately when Barney drinks from the ashtray, but this is actually a secondary setup-payoff built from Barney’s offended reaction to Moe’s suggestion that he’d steal booze. This leaves the thread of the initial setup active while the entire climax of the plot, Moe running to the Simpson home to threaten Jimbo, takes place. The return to Barney drinking beer from the tap becomes the now classic surprise-within-surprise reveal of a joke the audience didn’t realise was taking place.

When Moe says he’s gotta go check on Barney, it’s another obvious setup, but one that uses Moe’s diegetic recollection to carry the first by mirroring the audience being similarly reminded. This much setup is a lot of energy that needs to be paid off. The sight of him slumped backwards over the bar, drinking directly from the tap, is an innately comic transgression of standard behaviour, but fairly soft on its own. The great thing about a comic drunk is that the abundance of “crazy drunk stories” in society means Barney’s rubber band is a bit more flexible.

Barney’s heart stopping mid-binge is the extreme that this payoff needs, but it’s artfully given absurd reality through Barney’s equally absurd casual observations of his own condition. Nobody says “Uh-oh” if their heart stops. Nobody should casually say “THERE it goes” when it kicks back in. Each moment is deeply ridiculous but lent realism through a painfully awkward 3 seconds of still silence, a long time to be doing hard nothing in comedy. It’s insane, but it’s also the kind of thing you could hear about happening to Ozzie Osbourne and sorta believe. Maybe not exactly that way, you know, it picked up some telling over the years, but it’s not outside the realms of possibility.

Castellaneta’s voice work shines here. Part of Barney’s inspiration was a character called “Crazy Guggenheim”, a drunk played by Frank Fontaine on The Jackie Gleeson Show, whose drunk voice was more realistic with occasional flashes of Barney when he got excited. Barney largely works the opposite way, which what makes the delivery for these lines worth noting. Barney was more expressive when finding beer in an ashtray than when his heart stopped and started again. Toning Barney down, shifting him toward the normal, adds an absurdity highlight to the moments.

This is a large pattern, expertly masked behind key plot and a red herring smaller pattern, paid off in a beautiful structure of self-challenging absurd reality. A series great.

But the winner is…

A part of how “Homer the bad husband” jokes work without being painful or sad for the audience is that they are largely for us. Marge can cope with him like this in ways that his public displays make impossible because the eyes of others shine a light on the reality she hides. Homer’s public displays of bad husbandry are typically plot elements because of this need to be addressed. It takes skill to get a joke that uses this in a way that is at once extremely silly but subtle enough not to trigger that problem, which is why Homer arguing with his dog over a hammock is the winner.

The key to this is the absolute innocence of what Homer is doing here. Most people talk to their pets. Most people who have had their pets for quite some time get into conversations with them. It’s maybe mildly humorous on its own, but there is no comic negative, sin, or oafish transgression of social bounds like there was with his earlier hotdog pool.

The second element is that Ruth’s complaints about her ex-husband’s careerism positions the thing that Homer’s doing as the exact opposite of a negative. The quaint is now the homespun honesty of the simple folk, practically a virtue. But as Homer yells “My hammock!” at a dog that doesn’t really understand him, Marge is embarrassed because of a detail the audience shares with her: knowledge of how the opposite of Ruth’s statement is so true that Marge’s reality is even worse.

What Homer is doing is completely innocent. He’s guilty only because of a complex series of contextual elements perceived exclusively by his wife and the audience. Marge has been embarrassed by her husband again, but in a way that would never look it to the world. It’s the hotdog pool of the soul and a perfect demonstration of how the sublimely subtle can still whack you in the face.

Best Shot

The first pair of runners up both come from the basement and both relate to Bart’s eyes.

Last place is Bart’s rolled back eyelid scare. This one makes it partially because of the novel zoom, but mostly for being one of those times where the show demonstrates a more recognisably human component to the world’s physiology. Things like this are rare, usually only teeth and gums or the one-off moment with the fog in Treehouse of Horror V. The Simpsons’ cartoon style doesn’t leave much room for a sense of them as biological entities. I mean, where does Lisa’s hair end and skull begin?

A much more realistic animation style like King of the Hill doesn’t have the problems of heads and faces looking fundamentally wrong from certain angles, but then Mike Judge’s beady eyes and barely perceptible lids wouldn’t be all that interesting. The moment needs to stand out, and seeing winkled pink flesh and veins on Bart’s giant ping-pong ball eyes fucking stands out.

The second of the pair and next runner up is the zoom onto Bart’s eye as Laura comes up behind him. One of the fun things about the affordability of animation is that it allows for changes in the dialect of the show’s visual language that would be beyond the standard sitcom camera setup. The basement has already been a soft entry to horror film techniques as part of Bart’s prank. Moments like when he spies the sock use blue and black colours, visible but insufficient light sources, and long shots to shrink the children against the long shadows they cast. A vast difference from the standard blare of sitcom light and colour. These build to the payoff of Bart’s prank, which the episode then uses like a cat howling out of an opened cupboard.

Then a shape behind Bart begins moving toward him. Human, but slow and somewhat wrong. It’s groaning the word, “Friend”. Moments like this are impossible, but the idea that someone you hadn’t noticed heard your bullshit story and immediately ran with it is too improbable to beat the animal instinct of “AAAAH! MONSTERS!” The zoom to the eye is a horror classic because an isolated eye is both eerily alien but so recognisably expressive that a terrified one can transmit fear in a way that bypasses annoying human obstructions like common sense.

With Bart, his eye is a vast white circle, more alien and less expressive, but the zoom still works. His mind is collapsing into a single grim conclusion. He is a lone speck in a vast unknown, one that shouldn’t but does contain a monster. The moment isn’t meant to be scary, but it seriously applies all the tools to make something scary because taking it seriously helps the silly stand out.

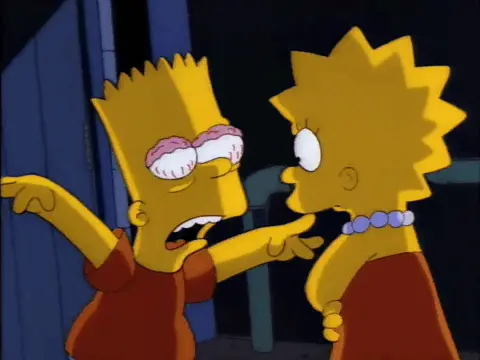

The next runner up is a portrait shot of Bart furious at his sister. This one scraped by on various details that come close to disqualifying it. It’s an otherwise unremarkable character shot and it’s so brief that it could almost count as a freeze frame. What gets it over the line is it’s there longer than a few frames, isn’t a weird smear, and perfectly encapsulates something very human: being accurately insulted.

There’s a depth to the fury that comes with this that the performative responses to perceived loss of status just can’t generate. Loss of status is something animals deal with. It creates animal symbols like bared teeth and raised voices. Accurate insults need language, theory of mind, and the other trappings that uniquely burden our species. The worst I felt it was watching the first run of season 16’s Future Drama with a friend, when Bart consoled Milhouse by saying, “Hey, I remember when you were a nerdy little fourth-grader. And now you're an emotionally crippled mini-Hulk.” My friend, who has known me since year 11, whipped around to point and laugh at me so hard he fell out of his chair. It was an armchair.

There are no comebacks for these. No clever ripostes. They are not the kinds of jabs one can feint but lightning bolts from the gods that strike mortals down.

This is not Bart’s angry face you see repeated every time the script calls for it. This is not something intended to convey a message to his sister. It’s fury, pure in its futility.

The next runner up is just an example of good blocking, it’s Bart watching Jimbo and Laura from the stairs.

Absolute freedom can paralyse creativity in a way that the need to work around restrictions does not. The need to frame actors in a space that exists independently of you forces thought about where the camera can go and what lighting is available. The camera in animation is a conceptual convention only, and while this freedom can be used creatively, the closer one gets to normality the more the standard shots become ingrained. Creative shots become an either/or situation with one being animated wacky and the other being sitcom dull, leaving a very thin band of creative cinematography.

Bart is the protagonist of this episode, but off-centre, shrunken and hidden behind stair bannisters, he is far from the protagonist of this shot. The teens, their awkwardly incomplete privacy, and the numerous narrative conventions this moment connects to are this moment’s whole world. The audience’s narrative perspective is bound to Bart, so framing it this way makes voyeurs of us too. We are outsiders to a scene we are inside, as awkward as a covetous ten-year-old boy.

The Simpson Neutral face, nominally inexpressive, is similarly effective here in its internal contrast. There is nothing explicitly sinister about this expression, there is nothing about it at all, but within this context those wide eyes and perfectly centred dots become a near Kubrick stare of intense, clumsy feelings.

It's an example of how to frame psychological perspective without using a point-of-view shot or inner monologue. Given that these are fairly simple to do in animation, it makes this shot a stand out.

But the winner is…

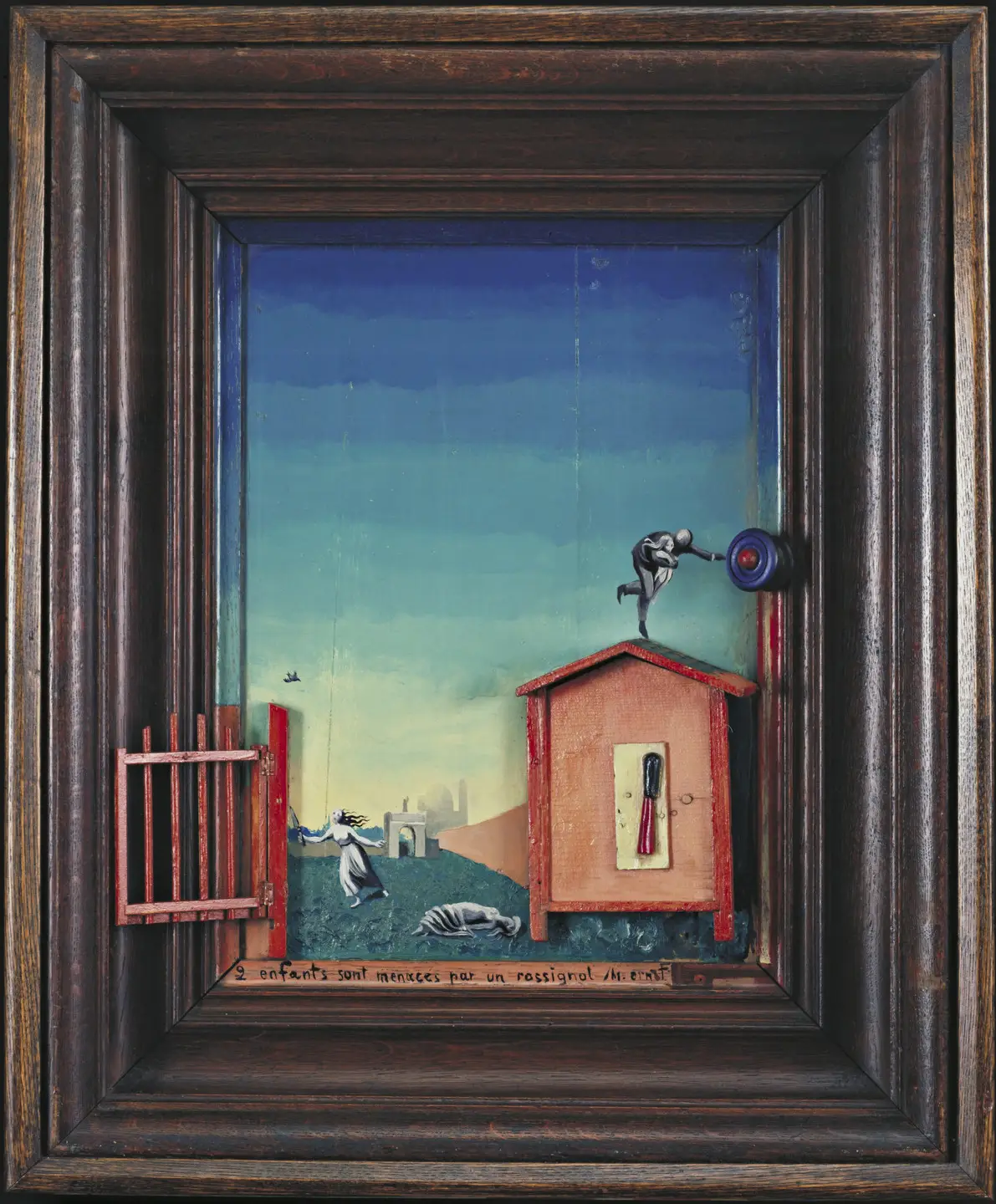

This is the Max Earnst mixed media surrealist piece called Two Children are Threatened by a Nightingale. The gate, little house, and doorknob are physical pieces of wood. The frame itself is a part of the overall piece, too. The effect of this mixing is a surrealist hallmark: a window into a dream, where the definitely real mingles with the definitively unreal.

The comic value of Homer being framed in all his ghastly splendour is obvious, but Homer’s hotdog pool takes on the qualities of a surrealist nightingale attack through animation serendipity. The husband of the happy couple on one side and the real estate agent on the other, each block the lower frame and sill of the window. The wall exists above, but now with the uncanny anxiety of a toilet stall whose lower gap is almost but not quite knee height.

Windows mark the difference between inside and out more than doors. Through a window, one can see the outside safe from their inside with a reassuring frame collapsing the vast exterior into a manageable glimpse. Magritte liked to transgress this by blurring the lines between window frame and picture frame, as in The Promenades of Euclid here. Inside, outside, and even within are blended into a surrealist whole that is ever so slightly unnerving.

With the frame lost, gone is the safety of demarcation. The outside and its Homer Monsters are bleeding into your lovely four-bedroom suburban. He is over there; but he is in here. The house is unclean. Not fit for sale. The eyes of the happy couple and the real estate agent are fixed on Homer, but he gazes at the sky in worship of the god of the oblivious.

Honourable Mentions

The way Lionel Hutz leans back in his chair while talking about his case against The Neverending Story always makes me chuckle. The way he stares off into the distance as he does it. His crinkled smile when he calls Homer the greatest hero in American history is another moment that sticks with me.

Another moment I like is the way Blue Haired Lawyer shouts, “YOUR WITNESS!” so dramatically. Reminds me a little of that moment in The Fifth Element when that guy screams “HELM 108” into the helmsman’s face.

Bart’s flashback to Jimbo bullying him is interesting because Bart’s in a different outfit and drawn slightly younger. I like small touches like that.

Dishonourable Mentions

Marge being allergic to shellfish is one of those pointless additions that only makes Homer’s goofy oaf husband into something cruel. Balancing Marge’s suffering has do be done carefully, and if she’s already being insulted there’s no reason to add injury.

Freeze Frame Fun

Comment on New Kid on the Block

To reply, please Log in