My Recollection.

The sound of Snake’s lights turning on. Stubbiness. Locker door opening.

There’s a moment in Preacher where Herr Starr is explaining to his troop of religious nuts that, in combat, you should always shoot the woman first. Any woman who has fought her way into some crack commando squad will have worked harder than any of the men and will be motivated by several layers of primal, societal, and personal needs to prove herself, making her the most dangerous thing on the field. He didn’t know it, but he was talking about Rebecca.

The pressures of existing in the underclass are excellent generators of prejudice. Omnipresent chronic stress drives a penetrating anxiety state that locks its citizens into animal immobility. Ignorance festers in the stagnant pool of people who see admitting a lack of knowledge as an unacceptable vulnerability, so the new becomes a threat, and ignorance becomes the safe option. With nothing else to claim for oneself, and a life circumstance that defines you as a failure, meaningful identities can only be drawn from something innate, like gender, or some vague concept of heritage. A word cannot define itself, neither can a group, so for there to be an in there must first be an out. Us versus them is the bread and butter of those left to eat cake.

The prejudices of the wealthy flow through arcane, impersonal systems that contain innumerable buffers against possible challenge. Are women incapable of mathematics? Are they just less interested? Do lagging social institutions apply pressures toward other roles? Does the existence of this doubt create an environment of self-fulfilling prophecy? This lady says she can do mathematics? Must be some mistake, send her to an asylum.

The laboratory of poverty produces cleaner results.

Can women fight? No. Why? Because they lose all the fights. This lady says she can fight? Must be some mistake, sen—oh fuck, she just beat the shit out of Neville. Rebecca was an exception to the rule in a situation where arguing against it ran you the risk of becoming just more proof in your opponent’s platform.

She looked like a gibbon, which I can say because one of the other aboriginal students said it first. She threw an encyclopaedia at said student, the M section, which, for those born into the digital age, was one of the big ones. Her gibbon-esque arms gave her the hurling arc of a trebuchet and the M section hit its target so hard some pages came out. For those born into the digital age, the pages weren’t just glued into these things, they were sewn. Sewn with actual thread.

The Teutonic women fought relatively hard but weren’t fun to fight because the Romans couldn’t exactly brag about beating a woman in combat. Even if that woman was batshit insane, fighting for her life, and swinging two axes. A similar attitude kept many from really challenging Rebecca when she went mental about something, and the assumption was that, sooner or later, someone would summon up enough “fuck it” energy to punch back and reassert an understandable hierarchy.

The thing about the strength disparity between men and women is that it’s largely the result of hormones. Testosterone goes to fucking work, but it also takes ages to arrive, meaning all the boys in Goodna’s seventh grade were lacking the advantage that made all the fights they saw at home so one-sided. So, when a weird Samoan kid called Danny, who was covered from head to toe in scars he said were from when he was thrown into a yabby pond by his uncle, decided that a fight with Rebecca was worth having, he didn’t realise he was going in with an undescended advantage.

Children have no idea how to fight, so all that’s left is nature. This means battles are wild swings for the head with little thought of takedowns or body shots. Danny’s hollow eyes and baffling yabby sacrifice origin story meant he was tough, but precocious puberty and a Reed Richards degree of reach made Rebecca’s head an impossibly high target hidden behind a wasp’s nest of stinging fists.

The resulting battle was like one of those episodes of Robot Wars where a shover went up against a spinning top. The way the shover would just bump into the whirling bommy-knocker appendage of the top, be briefly pushed back, then approach again to the roaring indifference of the audience. Danny would move in, cop a series of unanswered blows, move out, think about which colour was his favourite, and repeat the process. It was the strategic equivalent of Sun Tzu taking a shit and made the Zangief versus Dhalsim matchup laugh.

Rebecca lacked the strength for a knock-out blow, but Danny’s yabby-pinched face refused to tell him he was losing, so that corner of the library sat and watched Nintendo’s favourite boss fight play out in real life until a teacher’s aide finally heard the unmistakable PAPPITY-PAP-PAP-PAP of skeletal knuckles on haunted face.

Rebecca graduated both illiterate and undefeated. Nobody really held the loss against Danny, though, as he was still covered in gnarly scars and mostly didn’t blink.

The Episode.

I don’t remember much about watching Rian Johnson’s Brick in 2005, but I remember hating it. The sensation was like a post-it note that had once been attached to a manila folder marked “WHY YOU HATE BRICK (2005)” but had since come loose and was drifting about the ramshackle swamp shack I call a memory palace. I’d pick it up, look at it, remember I hated Brick, not remember anything else about it, and go back to trying to remember the name of the actor who played the weird heckler from Happy Gilmore.

After watching the wonderful Knives Out this year, I decided to go on a mystery binge, and came across reference to Brick. The post-it was still there, but the absence of anything attached to it was something the intervening 15 years had taught me to recognise as a potential problem. So, I sat down, re-watched, and loved every second of Brick. I didn’t even have to wonder why I’d felt otherwise.

Brick is near to a true noir story. The main character’s drive is to come to his own sad peace with a murder rather than find any justice for the victim. He is a ray of light in his environment only because his cynicism has not yet grown into the full-blown callousness of the indifferent authorities, cruel fellow citizens, and savage villains he is forced to deal with, though his navigation of this maze forces pitiless strategy. It is about brutalities made necessary by circumstance, made inevitable by fate, and the ones that weren’t necessary at all. It’s also set in a high school.

2005’s proximity to my own high school years made this an obnoxious clash. The assertion that these years, whether great or grim, were incredibly serious was not something I could tolerate hearing. Everything reeked of the overblown reminiscence of those who peaked early as they stared lovingly at images made large in the rear-view mirror.

But it’s not that. It’s a brilliant noir whose setting is, at most, a possible comment on how seriously we take those years. Like Bugsy Malone by way of the Cohen brothers, the juxtaposition creates a stylish magical realism, and the end result uses its character’s youth to add extra dimensions of pathos to its many tragedies and grimness to its moments of violence.

Separate Vocations looks like two stories that don’t entirely mesh. Bart’s turn as authoritarian law enforcer exists within a dreamlike unreality. His experience is a patchwork pastiche of police media: a car chase that borrows from Bullitt and Streets of San Francisco, lines from Kojack, glasses from Dirty Harry, scene transitions from Batman, and music from Beverly Hills Cop; he’s given a gun and fires it at Snake as the crazed criminal tries to run him down, only to be saved at the last moment; and his story is peppered with non-diegetic genre music, title cards with accompanying voiceovers, musical montages, and shots of him standing dramatically against glowing backgrounds. His story veers away from a comment or point, it contains no lessons for his character or his audience, it’s an assault of half-remembered references that don’t coalesce into anything.

Even without Bart’s as comparison, Lisa’s story is bleakly serious. Told an immutable physical trait, stubby fingers inherited from her father, makes her dreams of jazz stardom an impossibility and facing a Career Aptitude Test determined fate as a homemaker, she descends into a brief depression before regaining an identity through anger and rebellion. The story follows her as she lashes out through a series of escalating acts that eventually threaten her future.

Lisa’s life goals have never come up prior to this, so the audience gets all of a moment to even get to know them before the PG grittiness of her jazz dreams are burdened with the impossible task of being a suitable motivator for such a strong reaction. This leaves her revulsion at the life of a homemaker as the strongest point, because, whatever she wanted to be or do, housewife isn’t it. This then pushes her into a winnerless emotional conflict with her so-doomed mother.

Except her story doesn’t do either of these.

Lisa’s misbehaviour escalates, but it leads to nothing as the wrap-up of Bart taking the blame for her doesn’t leave her with any narrative conclusion. She’s just Lisa again. The stubbiness, the homemaker fate, and the ruined dreams are all forgotten. They aren’t challenged or broken through some realisation that the rebel this experience brought out of her is exactly the kind of person who can carve her own jazzy path through the world. As for the emotional conflict with her mother, it’s worth one joke that is, naturally, at Marge’s expense.

I typically watch an episode around 3-4 times, not including checking clips for quotes or moments, and I’d consider this the bare minimum for critical work. The first viewing is the “as normal” where I try to watch it without thinking or remembering too much, to let the show hit me as fresh as is feasible. The second viewing is the DVD viewing with the commentary on, which I added after the mistake with one of the wiki’s info on the cliff fall, and this is to get any little insights or titbits about the story. The third viewing is broadly analytical, where I start to tease out more critical elements, and the fourth is a detailed exploration of the episode in light of things I noticed in the third.

The third viewing is a great lesson in the way a first pass can leave you missing a lot. Firstly, it’s not two stories, it’s one story about coping with threatened identity that is (mostly) told with tremendous sophistication.

Starting at the school could be about Bart or Lisa, but the episode uses a shared narrative event, the C.A.N.T test, to bind the two. There have been stories about Bart and Lisa before, but this one is about the pair while not being about how they interact with each other, in fact, they have only two scenes together before the end, and don’t communicate in either. This superficial lack of connection through obvious narrative events creates a sense of separateness and part of the ultimate sense of failed cohesion, but more attentive viewings reveal more.

The opening shot of Bart’s class doesn’t cut to Lisa’s, the show uses a pedestal shot to move between rooms, it uses mirrored lines like, “we’re going to take a test” (and the identical student groan), and has the test play out sequentially across each class in order to establish a narrative symmetry that creates connection without contact.

Even when the pair are split into their respective threads, this symmetry is maintained through equality of the intensity of the inversion. The dreamlike quality of Bart’s intertextual cop procedural does not clash with Lisa’s sad realism, because each reflects their emotional reaction to their identity challenge. Bart’s highs are a place where the wild dreams of a ten-year-old boy—being given a gun by a cop, being given power, being the superhero with his own splash page—must stand in opposition to the lows of an 8-year-old girl—a future doomed by one event, resentment to the world that would allow this, near immediate descent into futile rebellion. Different worlds held in orbit of each other through an invisible weak force.

There’s a lot that can go wrong here, particularly in a 21-minute runtime, and double-particularly when a so-far absent narrative conflict that is teetering toward vast impersonal forces threatens to leave the episode pointless. The obvious point, conflict between the newly good Bart and the newly villainous Lisa, is effectively impossible due to the necessity of the sitcom narrative reset, so the story turns to Skinner.

Shifting perspective halfway through an episode is an easy way to break it, but the story’s split protagonist and undercurrent of alternative connection allow for such movement. Skinner is an extension of the already focal school environment, has a natural relationship to Bart and Lisa as characters, and a natural relationship to elements of their narrative. The way the shot moves from Skinner and the Puma to Lisa without edit continues the episode’s earlier connective work and establishes an indirect point of conflict between Bart and Lisa. A kind of tragic inevitability as opposed to a fight, which perfectly fits the episode’s construction.

But, while there is a lot of very impressive work, it’s not flawless. The story still ignores the cause of the conflict it resolves. Lisa’s fear at going too far is very genuine, but her immediate shift back needed more supporting tissue. Lisa’s reaction to the cigarette, a fear-driven return to her old self before a clearly hollow attempt at looking hard, is a dangling thread with too much focus to ignore and could easily have been wound into a setup for her snap back to goodness. Critique around the undone as opposed to the done is fraught with risk, as it can turn into meaningless hypotheticals, but when groundwork was already laid the partial effort highlights the fault.

Similarly, Marge’s presence in Lisa’s story disrupts the mirroring through Homer’s irrelevance to Bart’s. Again, mention is made of something that easily could have continued the connection—Homer having wanted to have been a police officer—but it goes nowhere. Not that the Bart/Homer connection was explicitly necessary to Bart’s story, but in light of the other work done, and Marge’s presence in Lisa’s, it becomes a noticeable gap.

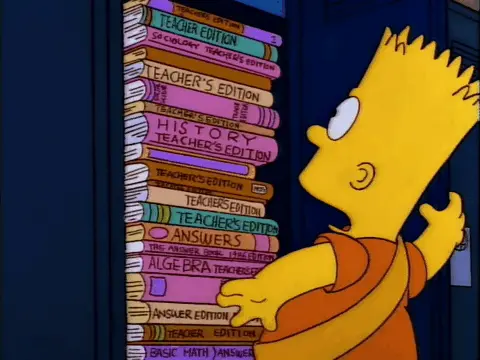

There’s also a case of “cross the streams” setup rejection in the way the theft of the Teacher’s Editions is an expulsion level threat for Lisa, but not for Bart. “In light of your recent service to the school” is a cover, but one that is a sloppy given the betrayal would warrant heavier punishment—like someone being an otherwise amazing day care worker just to molest kids, one cynically facilitated the other—and the implication that somehow Lisa’s stellar academic record wouldn’t warrant a similar balancing. But, unlike with Lisa’s abandoned jazz dreams, at least they went to the effort.

The value of critique in creative fields tends to be so distant from the standard user end that it can seem pointless, but even ignoring the meaningful improvement tools that critique provides for creators, understanding a few of the basics is good for anyone who even thinks about this a little. Taking a second look at something is the simplest of all ideas, but one that has great value as a missed piece can be the thing that pulls everything together.

Measuring faults is something that we instinctively do relatively, you react differently when your dog or otherwise functional adult son shit on the floor, but Separate Vocation’s faults follow it. At first pass, it’s a simple episode with simple faults: two stories that don’t quite fit at any point. On the second viewing, it’s an admirably complex work with disappointingly simple faults: a story cleverly stretched over two related but never quite touching narratives that do come together, just not well enough. Wiping with leaves when you’re stranded in a forest is understandable; wiping with leaves when you didn’t notice the toilet paper in your survival pack is idiocy. Even at its best, Separate Vocations has faults that were too easily fixed to be outshone by its recent service to the school.

It’s an odd case. Not a C student getting a C-, but an A student getting a B. The ultimate quality of this reality is a difficult thing to parse because it depends on your entry point. The leap from C to A is a bigger surprise than the slide from A to B, but if you enter at A, you’ll only notice a descent. Through this, though, and the other elements of the story, the one certain thing is that it’s a terrific critical tool.

Yours in being a salmon gutter, Gabriel.

Jokes, lines, and stray thoughts.

“I will not barf unless I’m sick” is a pretty funny chalkboard gag. Barf is kind of old slang now, so are chalkboards, really.

The reality level The Simpsons occupies is such a unique combination of cartoon and real. Few other animated series can genuinely get away with the old-style imagination bubbles, most use fades as the imposition of visible bubbles is a yard too far. It lets the show do little series gags like this opening surprise one that three separate fantasy sequences would make overdone.

The “things in the floorboards” gags are a bit like the couch gags in that the early series ones are fairly mundane. As a Queenslander, snakes in your floor isn’t even that unusual, my second cousin had a giant python living in his floorboards for a while. We used to rub it.

Opening shots are, for obvious reasons, keys to how to approach the episode. The pedestal shot and shared narrative event tell you that these separate events are connected.

Birgut sighting behind Lisa, she even gets to look disappointed at Lisa’s excitement over a test. I think this is one of the last episodes her and Doevid are in.

Krabappel’s rant is a beautiful piece of escalation. It’s hard to get these moments to feel genuine, but the brevity and performance help.

The ridiculously leading questions on the test are funny and work well because no attention is drawn to them.

Spurious rigour! Great comedy tool. Taking the silly seriously magnifies the silly.

The old guy is good, calling the test machine Emma is great.

I don’t think we ever took anything like this in Australia, at least I didn’t. They’re ridiculous things anyway, about as useful as a fucking horoscope.

“Salmon Gutter” we are into Retard Ralph territory here.

Milhouse as military strongman is funny, both for the juxtaposition and because that was even on there in the first place. It’s also another one of those jokes that more modern series would drag out. One thing I really love in these old episodes is the confidence to let a lot of this breeze by or get missed.

According to Wikipedia, “A systems analyst is an information technology (IT) professional who specializes in analyzing, designing and implementing information systems.”

Again, that Homemaker is even on there is funny.

Lisa’s revulsion at basically becoming her mother is such a good natural conflict for the pair. It’s rooted in so many ugly truths. Probably deserved its own episode.

Imagine a time when Homer was considered too fat for the American army and too dumb to be a cop.

Lisa having “jazz musician” as her life goal has some internal clashes. Her passion for music has certainly been seeded in episodes like Moaning Lisa, but she is such a fundamental goody-two-shoes that the inherently countercultural nature of jazz, and the accompanying lifestyle, just doesn’t fit with the rest of her current characterisation. Things like torrid love affairs and dying young border on Bartesque, while this girl was excited to take a test.

“Follow in my footsteps?” What footsteps, Homer? You have a job and a family, that’s most people’s footsteps. The bare minimum of western success is your footsteps. It’s a setup for a joke, and the howling wolves are always funny, but it’s good that it’s blown past quickly.

There’s a confident certainty to the scene Lisa has with the music coach and it’s that which carries this moment as a narrative function. There are so many basic things to pick apart with his assertion that Lisa could never be a great jazz musician, and most other narratives that approach things like this would address those. That this story can’t leaves this moment as a bit of a block, but the balls it has carries it.

Homer’s fingers twitching before he drops the beer can always cracks me up.

There are a few cutaways in this episode, and it’s indicative of a shift the series is taking toward a focus on humour. They’re interesting as they don’t clash with anything and aren’t otherwise unreal, that Homer is sitting at home having a beer isn’t the same as something Family Guy would do, but while they fit the reality they don’t fit any of the scenes. It’s something I can hear film teachers tell me not to ever do.

There’s a quasi-running gag of the police surprising Homer and him being guilty of some minor thing but it dies out fairly quick.

The Americanos are in a whir about copaganda like it’s a remotely relevant problem. It’s like getting beat up and then getting angry at a picture of knuckles. Do you know what else TV doesn’t depict accurately? Everything! It’s fucking TV. The problem, beyond the malformed nightmare they call a social structure, is that there are people whose only source of information on something is uncritically absorbed episodes of Cops. Fretting about TV shows when there are EVERY OTHER MORE IMPORTANT PROBLEM is classic poser activism.

“We club people with it” honestly, they could probably stand to return to the Old Ways. Dad copped a baton at the Springbok protest, back when this state was openly run by a Redneck Fuhrer, and there’s really less chance for serious injury than a bullet, rubber or otherwise.

“Polling the electorate” is a solid double entendre there, Lou.

I love that Quimby is with a girl, drinking, in a fuck-motel, but is still promising street names like the wooing part isn’t already over.

There’s a temporal continuity at work here, too. Shots like Lisa sitting at her log, with the night viewable through the window, give a sense of connection the usual leaping about doesn’t.

Similar work with Snake robbing Apu in the background of the police ride along. It works as a joke, but things like this also serve to tighten the narrative world.

Eddie’s version of the phonetic alphabet is great.

Another cutaway joke with relevant narrative connection with Apu liking the nylon rope. Oddly placed to interrupt the action of the police chase, which again feels like something film school would tell you to never do. I’d largely agree, while this doesn’t break anything, it doesn’t add anything, but fits okay due to the show’s focus and tone being comic. Something like this in a Bourne movie would stand out more as a hard error.

Things bursting into flames that shouldn’t is a Simpson classic, the milk tanker is probably the first go of it.

The green beetle that hits the milk tanker is a reference to a goof in Bullitt.

“Damn boxes”

Giving Bart a gun is a level of ridiculous that equals Bart being considered leader of the mob, but this gets away with it for a few reasons. It’s not an important narrative point, so it’s not wired into anything we’re supposed to take seriously. It’s over and done with quickly so it doesn’t linger long enough to be thought about. And it fits the presentation of Bart’s part of the story as being intertwined with his 10-year-old boy perspective. In more serious media, things like this would veer into free indirect discourse, the blending of authorial voice or audience perspective into a character’s without a clear delineation between the pair. More serious media could cast doubt as to whether the event even occurred like that, comedy can just play it for laughs.

Bart’s unreality is quite consistently supported throughout his side, this helps keep things like the voiceover and slight post-ad-break cutback as parts of a distinct stylistic choice instead of a mistake. It counterpoints Lisa’s realistic moping at her diary well.

“Waah, they can still hear things”

Wiggum has a kind of Wario quality to him that I’ve never really noticed before. A chance both have inspiration in Edward G Robinson.

Another shift to Lisa; another shift to the mundane and heartbreaking. Again, these things that would normally clash work when they are part of a deliberate plan.

There isn’t even the attempt to make Marge’s life look like anything but a shitful rut this episode. Not even lip service. It’s a side-effect, as she’s not the focus at all, but damn it’s cruel when you’re paying attention.

Maggie trailing fingerprint ink as she crawls away is one of those gags that takes something silly and makes it too familiar.

The “Homer eating the cake” gag is a great example of how to hide further surprise in a joke most could see coming. By this stage, viewers will at least suspect that it was Homer who ate the cake the moment Bart approaches. By having him up on the table eating the cake, it changes the joke into a surprise of extremity. Also, having reference to things that occurred in the past lets them be sillier in the same way Homer’s love letter to Marge in I Married Marge could be far smarter than words he’d ever be able to speak aloud.

The last shot of Homer on the table is a goodun, but it does make me wonder how Bart got the shots.

This is the second reference to Bart photographing his own butt. Now that I think about it, these photos were probably taken with the spy camera from Homer’s Night Out.

LOAD THE HEADCANNON

Bart does this a lot. Gets into photography but always has a shot of his own ass in the pile as he gets a sexual thrill from having others see it. People stop wanting to look through his photos, so he goes to ever more extreme lengths to get them seen and develops equally extreme excuses for how the images managed to end up in his otherwise innocent portfolio.

Going from a Bart moment to a Bart and Marge moment to a Marge and Lisa moment is another good use of available connective tissue. It highlights the inherent artificiality of most scene transitions and is a good thing to consider in your own works.

Christ, the Marge kicking. This scene is brutal because A: Marge fails to help her daughter AGAIN, B: this failure as a parent is never resolved, and C: yet another look into the woman Marge could have been had she not been crushed by the world around her. It makes the shot of her as President in The Last Temptation of Homer feel like a realistic look at what could have been.

“Principal of the Mountains” is so great, a lot of the little outlets Skinner has are great.

Really take note of how most shows just cut around and have stuff happen because the plot needs it to without taking the time to connect moments and have the results play out. Simple little things like having Lisa watching Skinner show his PUMA PRIDE are the kinds of beautiful little Chekhov’s guns that work far better than giant obvious ones.

Character inversion is a fun game but tricky to manage when you don’t have access to plot devices like Professor X’s brain exploding, so it’s seldom attempted let alone pulled off. That Separate Vocations manages it at all is impressive, and the degree to which it succeeds only impresses more.

Children are a great vector for things like this, too, as their emotional immaturity allows for complete identity crises without the complicating factors of audience expectations of adult behaviour.

I 100% dated the woman Donna the pink-haired bad-girl grew up into, several times. I regret every time but would do it again immediately because I am an idiot.

“Desecrate a helpless puma” and “The no-goodniks rule this school” and wonderfully constructed lines.

The shift to Skinner as a narrative anchor is good. It’s clever to use him as a point around which the plot orbits without making the plot about him exactly. A direct conflict between Bart and Lisa would need more time for the reset resolution to work and it would shift the theme of the story to familial conflict. This keeps their clash as something tragic we see coming but that gets averted at the last minute. It’s a real have your cake and eat it to trick.

It also allows the absurdity of Bart having Willy arrested enter the narrative without too much clash.

Love Willy getting arrested, some great Eddie and Lou faces here.

Bart is authoritarian, but there is little in his expression of it that indicates the expected love of power for its own sake. He never abuses it, which he could easily, he just voraciously enforces the rules as written.

“No more bullspit”

“That’s the meat of it, yes”

The blue spot in the trial scene is a reference to the William Kennedy Smith rape trial, which is grotesque for a show like this.

Steve Allen couldn’t say “aye carumba”

Are hall monitors real? Queensland schools are mostly outdoorsy, so there aren’t many halls to monitor.

“That belly ain’t gonna get aaany pinker” is a goodun.

The following wedgie on Milhouse is quality. Wedgies weren’t too common in Goodna as underwear use was inconsistent across the student body so reaching into pants could net you nothing but a handful of frightened bumcheeks.

Milhouse’s walk away is good.

Mentions of specific school terms are only ever trotted out as narrative necessity as they add a measurable time element to the show’s timeless universe.

Homer complaining about the yinyang nature of his own kids is funny. Forgetting Maggie is a tad far but also weirdly understandable.

Doevid behind Lisa and next to Chuck, making the blue ‘fro kid “The One Whose Nose Bleeds”. Wanna get a look at who’s behind them because Hoover’s seating chart lists them as “The Fat Kid”

Love seeing Ralph already eating the paste in this shot.

I’m calling it here: this is our first real Retard Ralph episode. The salmon gutter job is a doomed fate and the paste eating is the definitive tard kid behaviour.

Hoover just letting Ralph eat the paste is a general teaching tactic to keep the dim bulbs from being a drain on everyone else. By and large, mainstreaming is a good idea, but it requires a dedicated aide or specialist teacher, otherwise you’re just going to stress them out and draw far too much of the teacher’s time. Mostly, it’s a benefit to the rest of the class, who get to interact with and understand the different.

I fucking hated the forced crafts we had to do in primary school, just let me read or something.

“Whaddya got?” Brando’s line from The Wild One. The history of biker gangs and their relationship to the effects of early 20th century warfare on a generation of young men is an interesting area.

God I could use an angry, pink-haired Donna type about now an—no, nooooo, not again.

The moment with Lisa and the cigarette is very specifically focal. There’s the afterschool special music, the shot construction makes the offer an anonymous one, and there’s a brief return to normal Lisa. Lisa would be having an internal struggle with her new identity, and this struggle could easily foreshadow how she shifts back so quickly at the end. This scene is a part of that idea, but it trails off.

Love the Laramie Jr. cigarettes.

Skinner and Bart should have walked by the Bad Girls Bathroom to keep that connection going.

“Some corridors of this school you just never go down” another nicely silly little moment within Bart’s dimension.

The school evidence locker is a funny joke. At least, I assume it’s a joke. I don’t know what those American schools with their on-site police and mine-resistant war vehicles are confiscating to validate all that. Otherwise that entire situation is just degenerate madness.

These days, a fake plastic ass would be latex, and you could fuck it.

I fired a crossbow once and holy damn those things do NOT fuck around.

Lisa’s story gets a put on the back burner here, and I feel that she could have used her own moments in the montage of increasing rebellion. Her story is an emotional one grounded in reality, so it can survive on moments that we automatically fill in ourselves, but the lack of the mirroring present in the first half of the story is unfortunately noticeable.

“So, he didn’t have leprosy”

Mr Glasscock is a bummer of a name, but the shock would wear off quickly. Kids need novel stimulus to keep them going.

Bart’s shot as Hall Monitor, gazing out into the future against a shining background is a bit like the shot of Marge’s light bulb oven in that where it exists within the reality of the series is an interesting point. Is Bart imagining this? A bit like episode freeze frames that have since been turned into activities done by characters within the story world, seen by others etc, things like this are usually used for gags in modern shows.

Milhouse bullying Kernie is funny, made by Kernie’s reaction. Former victims can be the worst bullies too.

There are no teacher’s editions. In Australia, you’re expected to have a minimum of a bachelor’s understanding in your subject, and teaching is itself a master’s degree.

I mean, particularly with primary aged kids. That shit is easy. If I could, for five minutes, stand children that young, that would be the easiest job in the world. You need to know about 5 things per day and that could be done before class.

Ah, clapping dusters, another punishment lost to time. What do kids do now? Slam hard drives together?

It’s not the fault that Lisa and the cigarette is but something could have been made of her putting the Teacher’s Editions in her own locker as a manifestation of wanting to be caught. Otherwise, it’s just baffling. Granted, Lisa is not the practised criminal that Bart is, but still, one should be able to understand how not to get caught with stolen items of no actual value.

I like seeing more of the Springfield Elementary staff.

Krabappel went from being a Master’s graduate of Bryn Mawr to not having a basic enough grasp of any subject to fill about a quarter of a school day. I could teach a single day on any subject using just basic exploration approaches.

“Have I ever told you kids about the 60s?”

“I’ve got… to get… out of here”

“Calm blue ocean. Calm blue ocean. Calm blue ocean”

Ah, the classic Dutch Tilt, so simple yet so effective.

Some weird bonus officers with Wiggum and the hounds. They look too specific to be accidental.

Ha, police using a military grade vehicle to knock a library door down, what a humorous leap from reality.

That’s another cutaway, too.

I’d have added more about how Bart knows the Editions are still in the school.

The locker checking scene has a few jokes in it, like the cash pile, but the repeated shots of the opening and closing is a time waster when the story didn’t have time to waste. More time with Lisa was necessary and some more time with the emotional wrap up could have helped.

Axel F again, you don’t hear it around as much these days but, like the Eddie Murphy laugh, there was a time when you couldn’t escape it.

The shot of the Teacher’s Edition reveal is great. Having the top of the locker pinch into a vanishing point gives them an oppressive sense of height and power.

Where did Lisa come from?

“pre-fascist days”

“Even I had my limits” is a tough sell from Bart, all things considered.

This is actually part of the structural problem of this resolution. The threat to Lisa has to be a threat to Bart, but it isn’t for narrative convenience.

Lisa breaking down is very genuine, and the moment when Bart makes his decision is equally so.

“Saved this school 120 dollars” is good

That Skinner would immediately believe he was conned by Bart is very believable, but it only covers one part of the transition back to familiar character territory.

“Maybe I’ll just shut my big mouth” in the same rebellious tone is good.

Milhouse being the new authoritarian is a fun mini story considering his earlier demands for civil liberties.

There’s maybe 60 seconds of Homer in this whole episode.

“You’ve got the brains and the talent to go as far as you want” is half the necessary resolution. All Bart had to do to wrap the narrative elements up was mention that she could absolutely be a jazz musician if she did all this. Hell, add “in jazz” to the end of the sentence and it does the job.

Critique can generally only deal in what is within the presented reality, but with narrative these realities will necessarily use pieces of ours as building blocks. This becomes a kind of dimensional rift that makes issues of things like character stupidity, because we can, even though we haven’t seen it or anything, make expectations about behaviour based on our own knowledge. This is often done poorly, because people will usually mistake their understanding for a character’s, and will manifest as people whining more about what they would have done in a situation, regardless of whether a work has established what a character would have done. A lot of the worst and weirdly loudest idiocy is about this, with people coming up with entire hypothetical scenarios in their heads, being angry that those weren’t done, but never demonstrating how their ideas were meant to be a part of the work.

The conflict of Lisa having her dreams crushed is a present element within this episode, and it is forgotten. That is an error within the control of the work’s creators, hence the absence of things addressing it is relevant. A softer example is Lisa and the cigarette, which required demonstration of prominence through cinematic techniques to highlight how it stands out but connects to nothing while having the potential to connect to an existing plot element that, while not a hard error, is certainly a weakness.

7 replies to Separate Vocations

Preacher With A Shovel on 7th July 202007 Jul 20 said:

If you're still taking questions, I'd be curious as to your thoughts on how the Simpsons handled different nationalities, in particular the Irish jokes throughout the earlier seasons, or the Aussie episode.

Myself and my mates always get a laugh out of the ramped up Stereotypes in the Golden Age but I found myself baffled at the supposed attempt at a 'Representative' portrayal of Ireland in the Zombie Age with In the Name of the Grandfather.

Gabriel on 8th July 202008 Jul 20 said:

Questions are for the audio section, so that's where I'll address this.

Magnumweight on 7th July 202007 Jul 20 said:

Speaking from my own school experience, I didn't have hall monitors in any of my schools, least wise not made up of the student body, we just had assistant principals, constables and other general staff enforcing order. I feel it might have been a thing when the writers of the show were in school.

Funnily enough Lisa would get an episode where she takes up smoking, I daren't watch it but I know it exists.

My favorite thing bursting into flames lately was the nun in Brother from the Same Planet.

I've lately been watching episode through my phone with headphones and, much like the near constant bustling background noise in certain scenes of Deadwood, the headphones allow me to notice the prominent bongos in the opening theme that never seem to register when I watch it on the TV.

I still need to see Knives Out, I keep putting it off for some reason.

Gabriel on 7th July 202007 Jul 20 said:

It's fun, a lot of which is off the back of great performances and energy.

Magnumweight on 9th July 202009 Jul 20 said:

Finally watched Knives Out, enjoyed myself heartily. I feel it's one of those mystery films you can even go into knowing the twists because it's more about the craft than the strength of the reveals, which are still great, by the way. I feel it's a lot like The Nice Guys in that regard.

Alex on 7th July 202007 Jul 20 said:

I laughed entirely too hard at the Mr. Glasscock joke. I reminded me of an incident I heard a cousin went through.

I have a cousin. Her best friend lived across the street. They rode the same school bus, of course. It was normal procedure for the school bus driver to get a kid's name and contact information on an index card in case of accident or emergency. This bus driver tried to have them barred from the bus because she couldn't believe these 13-year-old girls' last names were Glascox and Seaman.

Gabriel on 7th July 202007 Jul 20 said:

Haha, oof.

Comment on Separate Vocations

To reply, please Log in